Wednesday, May 31, 2006

An End of Month Big Perspective

Since 1971 (N = 414 months), we've had 152 months in the Dow Jones Industrial Average that have touched 12-month new highs. This was the case during May. Twelve months later, the Dow was up by an average of 11.74%, with 120 months up and 32 down. That's quite a performance.

During the remainder of the months in the sample (N = 262), the Dow was no slouch, but not nearly so robust. The average gain was 7.01% (172 up, 90 down).

What this tells us is that, historically, strength has begotten strength in equities. It also points out a reality that we're apt to forget in the welter of negative news and scandals: long-term investment in American equities has, on balance, been a favorable proposition.

How about when the Dow has made a 12-month low? We've only had 41 months fit that bill. Twelve months later, the Dow was up by only 4.13% on average (23 up, 18 down), compared with an average gain of 9.25% (269 up, 104 down) for the remainder of the sample.

Buying a twelve month low in the Dow has, on average, led to underperformance.

There is an element of fear and volatility in the market that we haven't encountered for a while. And after we've made a 12-month high, probably any market looks overbought and ripe for decline. Nonetheless, these strong markets have been the ones with the most favorable outlooks 12 months out.

When the VIX Itself Becomes Volatile

What typically happens after a single day spike in VIX?

Since January, 1998 (N = 2108), we have had 27 occasions in which VIX has moved more than 15% in a day. All but one of these occasions were market declines. The next day, the market (SPY) was up by an average .37% (18 up, 9 down). That is much stronger than the average daily change for the entire sample (.02%; 1092 up, 1016 down).

Just as important, the five days following the VIX spike day showed much higher VIX (and price) volatility than average. The average daily VIX change over the next five days was 7.91%, and the average daily price change was 1.42%. Those compare with the averages for the sample of 4.13% and .89%, respectively.

After a five-day period of VIX volatility averaging 9% per day or more, the next day in SPY averaged a loss of -.18% (11 up, 15 down), but the next five days averaged a gain of .34% (14 up, 12 down). Once again, VIX volatility led price and further VIX volatility. Over the next five days, the average daily price change was 1.39% (vs. .89% for the sample), and the average daily VIX change was 7.14% (vs. 4.13% for the sample).

Overall, when the five-day average VIX change is 6% or greater (N = 287), the next five days in SPY average a gain of .67% (178 up, 109 down). This bullish tendency exists even when VIX levels following the VIX volatility are below 20. Interestingly, there is no edge one day out, however, in any of the data.

In short, volatility in the VIX begets volatility, with bullish implications five days out. That having been said, VIX percentage changes can be misleading, as recently pointed out by Adam Warner in his excellent blog. Nonetheless, look at the time periods with the highest five-day periods of average VIX change: April, 2005; September, 1998; March, 2004; and September, 2001. These were good times to buy stocks for an intermediate-term hold.

Tuesday, May 30, 2006

Profiting From Market Fear

Basically, I decided to stay short the market through the day as long as two conditions held: 1) emerging markets (EEM) were underperforming the U.S. market (SPY); and 2) VIX continued to make higher highs through the day. My reasoning was that, as long as the market was trading on fear--avoiding volatility and risk--we were likely to see a flight from equities overall.

Do fearful markets have a short-term bearish bias? I went back to March, 2003 (N = 815 trading days) and found 76 occasions in which SPY was down between 1.0-1.5%. Two days later, SPY was up by an average .26% (39 up, 37 down).

When we split this sample in half, however, based on VIX changes, a pattern becomes clear. When VIX rises strongly during the SPY decline (as has happened today), the next two days in SPY average a subnormal gain of .01% (15 up, 23 down). When VIX only rises modestly--or falls--during a decline in SPY, the next two days in SPY average a gain of .52% (24 up, 14 down).

It appears that the bearishness which leads to an extreme bidding up of options premiums during a decline tends to carry over in the short run, producing subnormal returns. When the market declines by an equivalent amount but options players do not bid up premiums aggressively, we're much more likely to get a reversal.

The willingness of market participants to take on risk may be an important variable in determining the likelihood of continuation of market moves.

Monday, May 29, 2006

Thoughts at the Edge of a Perfect Storm

I'm not sure American investors recognize how jammed the exits became when Mumbai's Sensex recorded its worst-ever point decline.

Or when investors took $8-9 bln USD out of Turkey's market--almost as much as they had attracted in capital last year.

Russia's stocks lost a quarter of their value in nine days.

In all, the recent losses in emerging markets were the greatest since 1998.

It's relevant to American investors, because daily changes in the emerging markets correlate about .74 with daily changes in the S&P 500 Index.

Banks are key to the contagion of financial crises.

Which is why the health of emerging market banks is of great concern in the face of growth problems.

Though South Africa was also caught in the downdraft, it remains confident that growth in China and India will continue to prop up its own and world economies.

There is hope that this is merely a correction brought on by rising U.S. interest rates and that the emerging market story has not come to an end.

No, the decline has not caused any aversion to investing in Asia.

Just witness the stampede for China's bank IPOs, which have attracted the participation of one in every five or six Hong Kong adults.

These are banks with untested risk management systems and a history of corruption.

And they propose to ramp up their loan issuance, even as China raises downpayments required for real estate transactions in an effort to dampen the explosion of (bad) loans.

For now, though, we're told there's no need for alarm in the Philippines and other Asian markets.

But, if I recall correctly, it was after the storm--and a sigh of relief--that the levees broke in New Orleans, in the face of multiple danger signs.

When everyone is drawing upon similar models, is it just a matter of time before they all head for the exits and create a Category 5 storm?

Note: More intermarket perspectives will be posted to the Trading Psychology Weblog later tonight.

Sunday, May 28, 2006

Asia's Enron

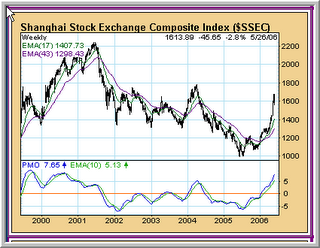

When you think of hot markets and rapid growth, what comes to mind but China?

But almost alone of emerging markets, Shanghai trades below its levels of 2001 and 2004.

Could the relative weakness stem from a glut of loans that threatens an already fragile banking system?

Could it be because many of those loans are non-performing and used for political purposes...whoops, no they're not.

Or maybe the market discounts those IPOs that have investors salivating and questions investor funds going to a banking organization that has no centralized computer system.

Alternatively, the market underperformance could reflect an awareness of a lack of intellectual property rights, which weakens the competitiveness of mainland firms.

Or maybe the problem is in the countryside, where rural loans have burdened the nation's second largest lender...

Or in Shanghai, where real estate prices are falling and controls on new mortgages are tightening.

Whatever the reason for market weakness, it doesn't seem to affect investors literally lining up to get shares in the new bank IPOs.

I don't think, however, that we'll see housing slaves line up for those shares.

Nor do I think that markets will be fooled in the long run when bad loans are moved from one state enterprise to another.

It didn't work in Houston, and I doubt it can work in Shanghai.

When Emerging Markets Submerge: Another Way Markets Confound Human Nature

Since late April, 2003 (N = 768 trading days), we've had 40 occasions in which EEM has been down by more than 5% on a 10-day basis. Ten days later, SPY has been up by an average 1.03% (30 up, 10 down)--much stronger than the average ten-day change for the sample overall (.43%; 459 up, 309 down). Big drops in emerging markets have thus, on balance, been bullish for American stocks in the near term.

How about when emerging markets are strong? We've had 114 occasions in which EEM has risen by more than 5% in a 10-day period. Ten days later, SPY was up by an average of only .08% (60 up, 54 down)--much weaker than its average performance. Strong emerging markets have thus led to underperformance among American stocks in the near term.

Readers of this blog will recall that, a while ago, I posted some findings regarding speculative vs. non-speculative stocks and the tendency of the former to lead the latter. EEM is one worthy proxy for those speculative issues. When the most speculative participants in the market are most bearish, it's best to step up to the plate. When those speculators are most bullish, it's time to take a few chips off the table.

It's another way in which markets confound human nature. We tend to extrapolate from the recent past to the near future, whether in predicting sports events, people's moods, or weather. Markets are one of the only spheres of life in which the recent past is an excellent predictor of the near-term future--in reverse!

Saturday, May 27, 2006

What We Can Learn From Relative Sector Performance

Readers of this blog will recognize that this line of research is designed to mirror the ways in which I have found highly successful market professionals to operate.

Let's begin with a simple example. Using ETFs, I divided the equity market into seven sectors: energy, finance, technology, consumer, health care, utilities, and raw materials. I then computed monthly correlations between each of the sectors on a moving basis and calculated an average correlation among all the sectors. This overall average correlation since March, 2003 (N = 807 trading days) has been .48.

Since March, 2003, we have had 97 days in which SPY has risen 2% or more on a five-day basis. Five days later, the average gain in SPY has been .25% (58 up, 39 down). This is not different from the average gain in SPY for the entire sample (.28%; 465 up, 342 down).

When, however, SPY has risen 2% or more *and* we have a high intercorrelation among the sectors (N = 48), the next five days in SPY averages a strong gain of .42% (34 up, 14 down). When SPY has risen 2% or more but the intercorrelation is low (N = 49), the next five days in SPY averages a gain of only .08% (24 up, 25 down).

It thus appears that strong rises are most likely to continue when the sectors are moving in concert. Returns are subnormal after strong rises when the sectors diverge relative to one another.

When it comes to declines, however, it's a different story. Since March, 2003, we've had 105 days in which SPY has dropped 1.5% or more in a five-day period. Five days later, SPY has averaged a gain of .99% (72 up, 33 down)--much stronger than the average gain for the entire sample as noted above.

When SPY has dropped 1.5% or more in a five-day period *and* the intercorrelation among sectors is high (N = 53), the next five days in SPY average a very strong gain of 1.44% (40 up, 13 down). When SPY has dropped sharply and the intercorrelation among sectors is low (N = 52), the next five days in SPY average a more modest gain of .54% (32 up, 20 down).

The bottom line is that when sectors are moving in unison, near-term results are bullish. Large gains tend to follow through with further strength (momentum effect), but large declines tend to reverse and produce large gains (reversal effect).

It does, indeed, appear that meaningful market edges occur when sectors deviate from their normal relationships with one another. More studies will follow.

Friday, May 26, 2006

How Pessimistic Are Traders When Markets Fall?

Since March, 2003 (N = 811 trading days), we've had 176 days in which SPY has declined by at least -.50%. Normally, such a large one day decline leads to favorable expectations in the near term. One day after SPY declines half a percent or more, the market averages a gain of .17% (109 up, 67 down). That is quite a bit stronger than the average gain for the rest of the sample of .02% (341 up, 294 down).

When SPY has dropped more than half a percent in a single day and equity put option volume declines on the day (N = 47; showing less bearish speculative interest among option participants), the next day averages a whopping gain of .40% (33 up, 14 down). When SPY has dropped by more than a half percent but put option volume increases (N = 129), the next day averages a gain of .09% (76 up, 53 down).

It thus appears that declines are more likely to reverse in the short run if they are not accompanied by expanded bearish activity among equity put option participants. It does seem as though large single day rises and declines should be viewed with special skepticism if speculative interest among option traders does not accompany the moves. I will be following and refining this research on the Weblog.

How Optimistic Are Traders When Markets Rise?

But what happens when the market rises by .50% or more and traders lose their optimism? I measure this very simply by tracking equity call volume changes from day to day. When SPY has risen strongly in a single day and call volume has expanded (N = 149), the next day averages a gain of .02% (86 up, 63 down). But when SPY has risen strongly in a single day and call volume has dropped (N = 55)--as happened on Thursday--the next day averages a loss of -.09% (22 up, 33 down).

Markets have tended to correct strong one-day gains, but this tendency is particularly pronounced when those gains have not been accompanied by commensurate speculative interest, as demonstrated by the actions of equity options traders. In my next post, we'll look at trader pessimism as markets decline.

Thursday, May 25, 2006

Finding Solutions to Your Trading Problems

My talk at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychiatric Association in Toronto yesterday afternoon concerned solution-focused brief therapy (SFBT). I continue to find it one of the most applicable short-term change technique to trading problems. It has also been used commonly and successfully with relationship and parenting concerns, as well as with overcoming personal barriers to reaching goals.

What makes the solution-focused approach unique is that it starts with the assumption that many problems that emotionally healthy people encounter are the results of their becoming too problem focused. In other words, once people become convinced that they have a problem, their subsequent actions unwittingly reinforce this problem, creating a damaging, circular pattern.

The classic example is the person who doesn't sleep well for a couple of evenings. He becomes convinced that he has an insomnia problem, and now starts worrying about his problem and taking extra steps to *make* himself sleep. All of these simply interfere with normal sleep processes and prolong the original concern.

This occurs with traders as well. Just as there can be chance streaks of wins, there are random losing streaks. Once traders define these as "slumps", they alter their trading, becoming overly cautious at times and overly aggressive to regain losses at other times. These changes to normal, good, planful trading only make the slump worse, creating the self-reinforcing problem.

The solution-focused approach gets away from this problem immersion and, instead, emphasizes *exceptions* to problem patterns. These are potential solutions.

For instance, it is very common that traders even in bad slumps make some good trades and have some good days and weeks. The solution-focused approach takes a hard look at these and pushes traders to identify what they're doing right when they're making money. These exceptions to slumps become positive behaviors that can then be codified as trading rules and mentally rehearsed before each day's trade. Pretty soon, the trader is doing more of what works and no longer feels in a slump.

The solution-focused approach suggests that sometimes the problem is not a deeply rooted psychological conflict. Sometimes we become too problem focused for our own good. No one ever succeeded merely by reducing or eliminating negatives. Our strengths are all we have to build upon.

Note: The Articles page of my personal site has free articles related to solution-focused techniques and trading.

Tuesday, May 23, 2006

Intraday Participation

The May 24th entry in the Trading Psychology Weblog offers a picture of market participation on a 3 minute basis leading up to the market's swan dive late in the afternoon. This chart tracks the number of advancing minus declining NYSE stocks. We began the day with strength, but advancers waned through the day *prior* to the large drop. Just as Monday's weakness could not extend to a majority of issues, Tuesday's rising tide could not lift all boats. That's a clear negative for this market and will have me looking once more for downside participation on Wednesday.

Monday, May 22, 2006

The Importance of Participation

The picture was mixed today, as we saw 4 stocks making new 52 week highs and 17 new lows for the session. Among smallcaps, it was 0 new highs and 16 new lows and among midcaps it was 1 high and 20 lows. All three of these do not represent an expansion of new lows from last week's worst levels. My Demand/Supply index is 43/50, which also does not indicate broad downside momentum.

Until we see broader downside participation, I am not selling lows here. I'll wait for participation to tip its hand before making that move. Falling tides, like rising ones, should affect all boats.

Sunday, May 21, 2006

The Market is Rigged Against Human Nature

Suppose you had two traders. One--a momentum trader--became optimistic and bought the S&P 500 Index (SPY) every time it rose in price for the day; the other--a contrarian--became optimistic and bought the S&P 500 Index (SPY) every time it declined in price for the day. Each trader held positions three days. What would be their return?

Suppose you had two traders. One--a momentum trader--became optimistic and bought the S&P 500 Index (SPY) every time it rose in price for the day; the other--a contrarian--became optimistic and bought the S&P 500 Index (SPY) every time it declined in price for the day. Each trader held positions three days. What would be their return?Since January, 1996 (N = 2584 trading days), the momentum trader would have an average return per trade of .01% (725 up, 617 down). The contrarian's average return would be .20% (679 up, 563 down). The trader who bought at the end of *every* day and held three days would have had a return of .10%.

In other words, simply by buying after a down day, the contrarian would have doubled the average return in the market.

By buying after an up day, the momentum trader severely underperformed the market.

Now you know why overconfidence in trading is the greatest pitfall of all. The market is rigged against human nature: getting excited after a rise and discouraged after a decline ensures that traders are on the wrong side of markets.

Saturday, May 20, 2006

We Gotta Hot One Today!

Well, how do we know when we got a hot trading day today? Hot for the trader means volatility. "I'll trade anything," one successful trader recently told me, "as long as it moves."

Since March, 2003 (N = 812 trading days), we've had 95 occasions in which the S&P 500 Index (SPY) has opened with a gain or loss exceeding .50%. That same day, the high-low range has averaged 1.46%, quite a bit higher than the 1.01% range for the rest of the sample.

Since 2005, we've only had 14 days in which SPY has opened with a move of .50% or more. The average range that day has been 1.20%, wider than the .90% average range for the rest of the sample. In current S&P point terms, that translates to a range difference of close to 4 points.

For similar reasons, since March, 2003, when VIX opens 4% or more from its previous closing level (N = 143), that day's high-low range averages 1.20%. The average range for the remainder of the sample has been 1.04%.

But how about when SPY opens with a move of .60% or greater *and* VIX opens with a move of more than 5%? Then, America, we got a hot one today! The average range (N = 15) has been 1.87%, which means that we have almost 90% more movement than the average market day. Even Simon might like that performance.

================================================

Later this AM, I will post the update to the Trading Psychology Weblog.

Friday, May 19, 2006

The Most Common Trading Problem

Studies in behavioral finance find that about 3/4 of all traders rate their prowess as "above average", despite the obvious reality that only half of us are better than the other half. This overconfidence, moreover, affects actual trading performance. Research by Terence Odean and colleagues finds that overconfidence affects frequency of trading, which in turn contributes to poor trading results. In one study of online traders, the group of traders favored high beta (volatile) small cap companies and tended to not diversify their portfolios. Their actual trading results slightly beat the small cap index, but after trading costs were factored in, they significantly underperformed the index. The most frequent traders were the ones who underperformed the index by the greatest margin.

One of my favorite studies of overconfidence came from the London Business School. Traders were shown price patterns and asked to figure out the market's next direction and indicate their confidence in their prediction. The price patterns were generated entirely randomly. The traders with the highest confidence in their predictions traded the most frequently and incurred the greatest losses.

A completely random trader--50% right, 50% wrong--who trades once a day will have runs of five consecutive winners about six times during a year. It is difficult to not think you have the hot hand after such a string, become overconfident, and raise your trading size. Of course, the random trader will have an equal number of strings of losers. That is likely to burst confidence and lead the trader to cut trading size--assuming, of course, that he's still in the game at that point.

Is it any wonder that traders seek help from coaches and psychologists? Few of those coaches and psychologists, however, will tell the trader the truth: You're trading random patterns and your problem is overconfidence in them.

Thursday, May 18, 2006

The Market is at an Important Juncture

* Across the broad universe of operating company stocks, we made 2026 new 20-day lows today--fewer than the day before.

* My Demand/Supply Index, which tracks stocks with very strong and very weak momentum, shows greatly reduced downside momentum. Demand was 42 today; Supply was 37.

* Today we had 13 new 52-week lows in the S&P 500, down from 23 the day before. We had 13 new lows in the S&P 600 small cap issues, down from 18 yesterday. We also had 12 new lows in the S&P 400 midcaps, down from 14 yesterday.

* Finally, a total of 15% of NYSE issues are trading above their 20 day moving average. The last times we've had readings below 20% have been October, 2005; April, 2005; August, 2004; and May, 2004. Those were excellent intermediate-term buying opportunities.

Yes, this may be the start of a new bear market. If so, we should see an *expansion* of new lows and *increasing* downside momentum. If we do not see a continuation of the late weakness tomorrow and continue to see new lows and downside momentum dry up, the odds of a market bounce will be greatly enhanced.

I will be following the new highs/lows and momentum studies carefully on the Trading Psychology Weblog in my next post Saturday.

What the Relative Range is Telling Us About This Decline

Yesterday, we had dropped 4.3% on SPY for the past five trading sessions. The five-day relative range was 2.39, which means that the range was more than twice the median five-day range for the past twenty days.

Since March, 1996 (N = 2551), when SPY has been down 4% or more for a five-day period (N = 120), the next five days in SPY have averaged a gain of 1.03% (75 up, 45 down). When we look at occasions when SPY was down more than 4% *and* the relative range was twice or more its median (N = 36), the next five days in SPY averaged a gain of 2.31% (25 up, 11 down). Conversely, when SPY was down more than 4% and the relative range was less than twice its median (N = 84), the next five days in SPY averaged a gain of only .48% (50 up, 34 down).

What this suggests is that periods such as the current one, in which a steep drop is accompanied by a sizable expansion in the relative range, yields superior returns in the near term. Perhaps this is because the large drop on a large range represents panic selling of short-term traders, creating value for longer timeframe market participants.

Wednesday, May 17, 2006

What to Expect After a Big Drop on a Big Relative Range

Since March, 1996 (N = 2553 trading days), when SPY has dropped 1.5% or more in a single day with a daily range of twice or more its 20-day average, the next day in SPY has averaged a gain of .55% (30 up, 19 down). When SPY has dropped 1.5% or more in a day with a range of less than twice its average, the next day in SPY has averaged a gain of .15% (99 up, 81 down). It thus appears that a single day drop on a large range tends to bounce the following day.

Finally, combining this analysis with my last one, I found 24 occasions in which we had a one-day drop of over 1.5%, a five-day decline of over 3%, *and* a one-day relative range greater than twice its twenty-day average. Two days later, SPY was up by an average 1.02% (17 up, 7 down)--much stronger than the average two-day gain of .07% (1360 up, 1193 down) for the sample overall.

In all, it appears that we tend to get a bounce following a large decline during a weak week when the daily range is extended.

I will post details of the market drop later tonight in the Trading Psychology Weblog.

What To Expect After a Weak Day and a Weak Week

I will post an initial analysis here and further analyses tonight and tomorrow AM. Tonight's Trading Psychology Weblog will also contain a large amount of material on the recent market weakness and what it means for the market's near-term course.

First off, we had a drop in SPY of approximately 1.9% today, with the last five sessions giving us a decline of 4.3%. Since March, 1996 (N = 2553 trading sessions), we've had 229 days in which SPY has dropped by 1.5% or more. Two days later, SPY has been up by an average of .43% (126 up, 103 down). That is stronger than the average two-day gain of .07% (1360 up, 1193 down) for the sample overall.

When we divide the weak S&P days in half based on the performance of the past five trading sessions, we see a clear pattern. When S&P is down by 1.5% or more *and* the five-day S&P is strong, the next two days in SPY average a loss of -.06% (53 up, 61 down). When S&P is down by 1.5% *and* the five-day S&P is also weak (as at present), the next two days in SPY average a gain of .91% (73 up, 42 down).

That suggests that a very weak S&P day only has obtained a bullish edge if it occurs in the context of a weak five-day period.

Stay tuned. I will be spitting out further studies later tonight.

A Momentum Pattern That Seems to Work: The Relative Range

Suppose we look at the day's trading range as a function of the median daily trading range for the past 20 days. This relative range statistic tells us when a market move is very large or small compared to recent volatility norms.

I focused especially on large relative range days, because those also had the potential to be breakout days and perhaps lead to some momentum follow through. I also focused on the relatively low volatility market we've had since January, 2004 (N = 595 trading days); later explorations will look at a wider timeframe.

Since January, 2004, we've had 32 days in which the two day relative range in SPY exceeded 1.70 (i.e., today's range exceeded the median two day range by 70% or more). This was the case at the end of last week with the large drop. Two days later, SPY was down by an average -.10% (13 up, 19 down), which is weaker than the average two-day gain of .05% (320 up, 275 down).

Here is the interesting part, however. When the second day of the large two-day range was up from open to close (N = 11), the market was higher two days later on 10 of those occasions. When the second day of the large two-day range was down from open to close (N = 21), the market was down two days later on 18 of those occasions.

It thus appears that a large relative range leads to short-term price continuation in the direction of the large range move. I will need to explore this over a longer time frame and under different market conditions to determine whether this is a general or local pattern.

===========================

An observation from the Weblog: Energy stocks are actually below their levels from last January. Could it be that the fortunes of major oil companies will increasingly diverge from oil prices as countries nationalize their reserves?

Tuesday, May 16, 2006

Self-Inflicted Problems of Trading Psychology

Many psychological problems I encounter among traders--professional as well as novice--are self-inflicted.

I say this, not to blame victims, but to call attention to the fact that two trading practices seem to lie at the heart of at least half of all the problems I see among traders:

* Quantum leaps in trading size - Traders increase their size in large proportional increments, creating P/L swings that feel large and that interfere with calm, rational decision making. It may not seem to be a large shift when you raise your size from five contracts to ten, but that doubling of size--and the resulting doubling of P/L swings--may feel much different than it looks on paper.

* Departures from prudent risk management - This occurs particularly when traders are up or down a great deal of money on the day. Traders become overly aggressive to get their money back, or they become overly risk averse when they're down. Similarly, when up money, traders become risk-seeking with house money or fearful of losing their gains.

Very often, these problems go hand in hand. Large changes in trading size lead to outsized gains and losses and departures from prudent risk management. These large emotional swings are processed by the mind in a manner similar to psychological traumas, creating very negative (and difficult to change) conditioned responses (different in degree, but not kind, from post-traumatic stress reactions).

My heartfelt message: Treat size with caution. Increase size incrementally, ensuring that trades don't feel different when you enter and manage them. The best treatment for trading psychology problems is preventive medicine.

===================================================

We've had a flat two-day period in SPY, a pattern which we recently saw leads to modestly bearish expectations.Tomorrow AM, I'll begin posting on the topic of volatility and its relationship to near-term price change.

VIX and Put/Call Ratio: How Are They Related?

I received a few emails regarding the relationship between the put/call ratio and the VIX as measures of sentiment. I decided to create relative versions of both indicators, by evaluating each as a proportion of its 20 day moving average. Interestingly, the correlation between the relative VIX and the relative put/call ratio since March, 2003 (N = 805 trading days) has only been .41. That means that about 16% of the variance in the relative put/call ratio is attributable to the relative VIX and vice versa. While the two indicators are related, they are not measuring the same thing.

What has made the recent time period significant--particularly this past Friday--is that the relative VIX was quite high (19% above its average) *and* the relative put/call ratio was quite elevated (54% above its average). Since March, 2003, we've had 33 occasions in which the VIX was 15% or more above its average. The next day, SPY averaged a gain of .35% (23 up, 10 down)--much stronger than the average one-day gain for SPY of .06% (448 up, 357 down).

A median split of the data based upon the relative put/call ratio was instructive. When the VIX was more than 15% above its average and the relative put/call ratio was high, the next day in SPY averaged a gain of .49% (13 up, 3 down). When the VIX was elevated and the put/call ratio was low, the next day in SPY averaged a gain of .21% (10 up, 7 down). Clearly, the upside edge is greatest when VIX *and* the put/call ratio are elevated, as we've seen recently. Enhanced volatility and enhanced pessimism, when they occur jointly, seem to offer superior near-term rewards.

Monday, May 15, 2006

Relative Price

Do Trading Edges Last Forever? A Look at VIX

As I indicated in my responses to these questions, the answer to this question differentiates those who are searching for universal relationships in the market (mechanical systems that will work in any market condition) from those who continuously model and remodel markets to find local regimes (relationships that wax and wane over time).

Here's a practical example: Let's say that I am trying to predict a person's behavior in response to a piece of news. I could take a large past sample of behaviors following receiving news and use this to make my prediction. That would be a linear approach, looking for a universal relationship between news and behavior.

A different approach might say: The person's behavior in response to news will depend on their moods, which come and go. So I will have one prediction if the person is in a good mood, another prediction if mood is neutral, and a different prediction when the person is in a bad mood. My samples for analysis will consist of only good mood occasions (for my first model), neutral mood occasions (for the second model) and bad mood occasions (for my third model). This would be a non-linear approach, finding different relationships between news and behavior as a function of mood.

Consider that volatility and trending are variables that define market mood. If that is the case, the non-linear historical modeler would argue, relationships between indicators (such as the VIX) and future price change should be specific to the mood (market conditions) at the time. There is no strong, universal predictive relationship across all moods (market conditions).

Because of this, no trading edges last forever in the view of the non-linear modeler.

Let's take the relative VIX as an example. In my previous post, I found that, when the VIX exceeds its 20 day moving average by 15% or more, there is a bullish edge going forward. That analysis covered March, 2003 to the present. But let's extend the analysis from January, 1998 to the present (N = 2124 trading days).

During that time, we have 159 occasions in which the VIX exceeds its 20-day moving average by 15% or more. If we divide the sample in half based solely on time, a pattern emerges. Between January, 1998 and March, 2001 (N = 80), after such a VIX spike the S&P 500 Index (SPY) was up by an average of .62% two days later (51 up, 29 down). This outperformed the overall sample, which shows a two-day average gain of .04% (1111 up, 1013 down).

From March, 2001 to the present, following a VIX spike (N = 79), the market was up by an average of only .05% (43 up, 36 down) two days later. This does not outperform the overall market.

In other words, the relative VIX gave us a bullish edge between 1998 and early 2001, but not afterward. From the earlier post, we saw that the VIX spike gave a bullish edge from 2003 to the present. As you might imagine, the same VIX spike provided no edge--and actually led to a slightly bearish outcome--during 2001 and 2002 (-.07%; 25 up, 25 down).

We could come to two conclusions about the VIX from this little investigation: 1) it is a poor indicator, since it does not yield consistent predictions over time; or 2) it is a good indicator, as long as we utilize it when current market conditions suggest it will be effective. Clearly, this site takes the latter approach. It's not a foolproof method--market cycles can possibly change without our being aware of it at the time--but until we find the perfect, universal indicator, it might just be the best we can do in the face of complexity and uncertainty.

Sunday, May 14, 2006

Spike in the VIX: Is There an Edge?

On Friday, the VIX closed 18% above its 20 day average--a substantial spike. Since March, 2003 (N = 804 trading days), we've had 32 occasions in which the VIX has closed 15% or more above its 20 day average. Two days later, SPY has averaged a gain of .58% (21 up, 11 down). That is much stronger than the average two-day gain of .12% (437 up, 367 down) for the sample overall.

This is consistent with Larry Connors' research, which suggests that VIX elevations lead to superior returns in the near term.

Saturday, May 13, 2006

Two Consecutive Broad Declines: What Comes Next

The next day, the S&P 500 Index ($SPX) was up by an average .59% (9 up, 4 down)--much stronger than the average daily gain of .04% (2174 up, 1950 down) for the sample overall.

Two days later, the S&P was up by an average 1.37% (10 up, 3 down)--considerably stronger than the average two-day gain of .08% (2209 up, 1915 down) for the 1990-2006 sample.

What that tells us is that two consecutive down days of very negative breadth is a rare occurrence. It is also interesting that 7 of the 13 next day occurrences led to price changes of greater than 1%, suggesting that volatility follows broad two-day declines. Looks like it might be worth looking for buying setups on Monday and watching for a carryover of volatile action.

Friday, May 12, 2006

Ten Questions That Go Bump in the Night

Would 80% of traders make money instead of losing it by placing trades through "enrichers" instead of "brokers"?

Why do people who offer programs on making a living from trading make their livings from offering programs?

Why do beginners think they'd have an easier time beating professionals at trading than at golf, boxing, racecar driving, or chess?

Why are so many market newsletters bullish or bearish, when the most common market outcome is little or no change?

Why, in Dr. Brett's surveys, do three-quarters of all traders rate themselves above average?

Why are there no books on mastering the mental game of surgery or ballet?

What happens when contrary opinion is the dominant school of thought?

Why do trend followers follow trend following once it goes out of favor?

If exchanges make more money than brokers; brokers make more money than market makers; and market makers make more money than traders, is the answer to success in the markets to always have people who are your customers?

===========================

I want to thank readers for their interest in the new highs/new lows stats mentioned in my recent article. I'll continue to post those on my Weblog. Have a great weekend--

Brett

Big Drop, Little Fear: What It Means

Interestingly, Thursday's drop of over 1% on SPY occurred with an equity put/call ratio of only .65, one of the lowest readings we've seen on a day with such a drop since March, 2003 (N = 803).

When we've had a down day in SPY of more than 1% (N = 73), the market two days later has averaged a gain of .28% (37 up, 36 down). That is stronger than the average two-day gain of .12% for the sample overall (437 up, 366 down).

When we divide the sample in half based on equity put/call ratios, however, a pattern emerges. A large SPY drop with a low put/call ratio, such as we saw on Thursday, results in an average gain of only .02% (17 up, 20 down) two days later. When the SPY drop occurs with a high put/call ratio, we see an average change in SPY of .56% (20 up, 16 down).

Returns appear to be superior when declines are accompanied by fear and pessimism--something we didn't see on Thursday.

Thursday, May 11, 2006

Relative Movement: A Different Way of Looking at Strength and Weakness

One way to adjust for these volatility differences is to measure a day's movement in standard deviation units. What I did was create a moving 60-day window for SPY and calculate the standard deviation of daily market moves. I then calculated each day's movement as a multiple of that 60-day standard deviation.

It might surprise you that today's decline was a drop of 3.39 standard deviation units. Since April, 1996 (N = 2520 trading days), we have only had 86 such declines. So while it might seem as though today's drop was not huge, in relative terms it was quite a drop.

Since 1996, the day after a drop of 3 or more standard deviation units, SPY has been up on average .16 standard deviation units (46 up, 40 down), stronger than the average gain for the sample of .05 units (1311 up, 1209 down).

When we look at the most recent data, however, a different pattern emerges. Since 2003, we've had 26 drops of 3 or more standard deviation units. The next day, SPY has averaged a loss of .51 units (11 up, 15 down). From 1996-2002, the next day change in SPY after a big relative drop has been a rise of .45 units (35 up, 25 down).

Psychologically, we may respond more to the relative size of moves than their absolute magnitude. That reaction may be particularly magnified during low volatility market periods, leading to next day continuation of weakness.

Can Small Caps Play Catchup One More Time?

During our recent three-day flat period, the Russell has been down over .60%. When SPY has been flat on a three-day basis, but Russell has been down more than half a percent (N = 28), the next three days in SPY average a gain of .20% (17 up, 11 down) and the next three days in IWM average a gain of .36% (15 up, 13 down). Indeed, the last eight times we've had a flat SPY and weak IWM, the IWM has been up on seven of those occasions three days later--and six of those occasions have featured a rise of a full percent or more.

Flat periods in SPY appear to lead to underperformance when other major sectors are flat or strong. When those other sectors are weak, the returns have been normal. Recently, we've seen IWM play catchup when it has underperformed SPY in a flat market. Such a broadening of market strength would be a plus for this market. As my Weblog notes, we're seeing weakness in the new high statistics across the market sectors.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

A Valuable Lesson From Today's Market

A trader called me before the Fed came out with their statement and asked if I had an opinion about what the market was going to do. I gave the answer that I've mentioned quite a few times on my personal site: Keep an eye on interest rates and the dollar. If they don't sustain directional moves after the news, it means that the markets are not repricing assets as a result of the Fed statement. Under those conditions, stocks may jerk up and down, but are less likely to trend.

Conversely, if bonds/notes and the dollar make strong directional moves after the Fed news, I explained, it means that the markets are pricing in new valuations, because the Fed news is real news. That would be more likely to lead to stock index repricing as well.

As it turned out, the dollar was weak but could not sustain a trending move relative to the Euro, which traded first below, then above, and then below again its average price for the day. The 10 year interest rates spiked higher on the news, then stayed firmly in their multiday range. Not surprisingly, stocks closed near their average price from the previous day.

The lesson is this: There's nothing wrong with predictive models--including the kinds of predictive looks I take in this blog. Ultimately, however, it is more important to *identify* what markets are doing and *understand* why they might or might not be moving. The trader who saw the bigger picture was more likely to fade the overreactions to the Fed news than the trader than the trader who got caught in a directional opinion.

Oil, interest rates, currencies, other commodities, international markets: all compete for assets and all are inextricably interrelated in a world economy. Today offered a good lesson: The big picture matters--and sometimes nothing is happening in the big picture.

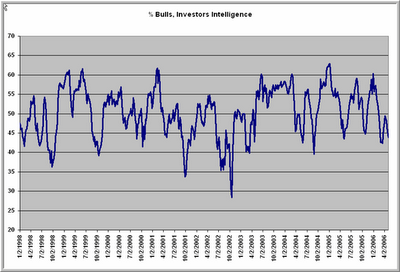

Where Are All the Bulls?

Here is the % bulls from the Investors Intelligence survey from 1998 to the present. Dips below 40% have been great buying opportunities; returns have been subnormal when we've exceeded 60%. We briefly hit that 60% mark at the beginning of the year, but look at how bullishness has tailed off even as large caps have been making new highs. Once again, it's a sign of more worry than complacency in this market.

Tuesday, May 09, 2006

A Market That Isn't Looking Complacent

I'm pleased to announce that my new book, Enhancing Trader Performance, is coming along well and will be out this fall.

Here's an investigation that extends a finding from an earlier study. That posting found market underperformance when flat markets were accompanied by falling VIX values, rather than a rising VIX. In that study, I looked at the most recent market day and what happened subsequently. Now we'll look at two-day patterns, given that we've been relatively flat in SPY for the past two days with a VIX that has risen over 3%.

Since March, 2003 (N = 801), when SPY has been up or down within a .10% range over the past two sessions (N = 74), the next day in SPY has been down by an average -.07% (36 up, 38 down). That is weaker than the average one day change for SPY (.06%) for the sample overall.

When the flat two-day period in SPY has occurred during a rising VIX (N = 37), the market has averaged a gain of .07% (19 up, 18 down)--not greatly different from its average performance. When the flat two-day period in SPY has occurred during a falling VIX (N = 37), the market has averaged a loss of -.20% (17 up, 20 down), much weaker than average.

Once again, we see that flat periods tend to be associated with subnormal returns, but that this is particularly the case when VIX levels (investor fear levels) are falling. When investors are more skittish--as they might be prior to the Fed news in the current situation--outcomes are much more normal.

Interestingly, over the past 10 trading sessions, we're up well over 1% in SPY, but VIX levels are higher now than back then. I find this lack of complacent sentiment interesting, particularly given the fact that we're at bull highs in the large caps.

Monday, May 08, 2006

Rest Day After Strength: What Comes Next?

I went back to March, 2003 (N = 800) and identified all occasions in which the most recent trading day in SPY had a narrow range of .50% or less (N = 53). The next day in SPY averaged a loss of -.13% (21 up, 32 down), much weaker than the average gain of .06% (446 up, 354 down) for the sample overall.

When the narrow day followed two days in which SPY had been up more than .50% (N = 25) (such as is the case at present), the results were even more bearish. The next day in SPY averaged a loss of -.16% (9 up, 16 down), with weakness extending three days out (-.28%; 9 up, 16 down).

It thus appears that a narrow day after a market rise is not a pause that refreshes, but rather may indicate an exhaustion of the rally. Incredibly, 10 of the last 11 times this pattern has occurred (since 2/05), the market (SPY) has been down three days later.

Sunday, May 07, 2006

Five Straight Up Weeks in the Dow: What Comes Next

It turns out that the event is quite unusual: it's only occurred 69 times since January, 1978 (N = 1474 weeks). During that time, the average five-week change in the Dow has been 1.03% (910 up, 564 down). When the Dow has been up five weeks in a row, the *next* five weeks have averaged a gain of only .02% (39 up, 30 down).

Just out of curiosity, I looked at what happens after we have five consecutive *down* weeks in the Dow. That is an even more unusual event (N = 24). Five weeks later, the Dow averages a healthy gain of 2.0% (18 up, 6 down).

In short, buying into five consecutive weeks of strength has led to underperformance five weeks later; buying into five consecutive weeks of weakness has led to outperformance.

But wait, there's more:

- Between 1978 and 1982, we had five periods of five consecutive up weeks in the Dow only five times. Four of those times, the Dow was down five weeks later.

- Between 1985 and 1987, we had 11 periods of five consecutive up weeks in the Dow. Eight of those times, the Dow was up five weeks later.

- Between 1995 and 1998, we had 19 periods of five consecutive up weeks in the Dow. 17 of those times, the Dow was up five weeks later.

- Between 1999 and 2002, we had 10 periods of five consecutive up weeks in the Dow. 9 of those times, the Dow was down five weeks later.

You get the idea: We're more likely to have five consecutive up weeks in the Dow during bull markets than bear ones, but when we do get five up weeks in a row in those blue chips, the odds of being up the *next* five weeks are much greater in bull markets than bear ones.

Which brings us to the 2003 - 2006 period. We've had seven periods of five consecutive up weeks in the Dow during that time; five of those periods, the Dow was up five weeks later.

But the last two occasions have been the two times when the Dow has fallen after five consecutive up weeks.

The bottom line: If this is truly an extension of the bull market, we should see the market hold its recent gains. If we return to the recent trading range that we broke from on Friday, I'm willing to entertain the notion that the bull is aging. I'll be tracking this on my personal site; also check out my column for Trading Markets on Monday.

Saturday, May 06, 2006

Three Pieces of Market Wisdom

1) The market provides its greatest edges following unusual recent market occurrences;

2) To determine your edge, investigate what the market has done in the past following such unusual occurrences;

3) To investigate what the market has done in the past following such unusual occurrences, investigate past time periods that have been similar to the present period. Don't use bear market data to investigate an event occurring in a bull market, etc.

Following up on a comment from Paul, who by the way has an excellent blog himself, I'd like to illustrate these principles.

Friday's response to the economic news was unusual. We opened on SPY higher than the highest high of the past five days. That has only occurred 57 times since March, 2003 (N = 799 trading days).

To determine if there was an edge after such a robust open, I looked at those 57 occurrences and found that the market, from the strong open to the close, averaged a loss of -.20% (27 up, 30 down). This is much weaker than the average open to close change of .02% (425 up, 374 down) for the sample overall.

But, wait. I noticed that 30 of the 57 occurrences took place in 2003 alone. That was the most robust period of the bull market, so it makes sense that we'd have a number of strong opens. But that was also the least typical part of the bull market, because of the higher volatility and trending during that time.

So, in accordance with the third principle, we look at only those occurrences of opens that are above the high from the previous five days since 2004 (N = 27). Lo and behold, we find that the average change from open to close was .07% (18 up, 9 down). And, from the open to the *following* day's close, we averaged a strong gain of .30% (18 up, 9 down)--much stronger than the average open to next day's close of .08% (438 up, 361 down) for the sample overall.

There are two lessons here:

1) Look for your edge in places where other traders aren't looking: when unusual events are occurring, but might be recognized as unusual at the time.

2) When you think you've found your edge, delve deeper. Sometimes the edge you think is there has gone away and, more recently, has been replaced by a very different pattern.

On my personal site tonight, I will post an entry to the Trader Performance page that elaborates some of these issues.

Friday, May 05, 2006

What's Really Happened While the Dow Made New Highs

We had 41 new 52-week highs in the S&P 500 Index, down from 80 two weeks ago.

We had 61 new 52-week highs in the S&P 600 Index of small cap stocks, down from 100 two weeks ago.

We had 36 new 52-week highs in the S&P 400 Index of mid cap stocks, down from 62 two weeks ago.

We had 1 new 52-week high in the Dow 30 Industrials, down from 5 two weeks ago.

As the Dow made new highs on Thursday, momentum among stocks in the major averages was down, as well:

We had 62% of S&P 500 stocks above their 20-day exponential moving average, down from 80% two weeks ago.

We had 63% of S&P 600 small cap stocks above their 20-day EMA, down from 78% two weeks ago.

We had 56% of S&P 400 mid cap stocks above their 20-day EMA, down from 70% two weeks ago.

We had 70% of Dow 30 Industrial stocks above their 20-day EMA, down from 90% two weeks ago.

Growth stocks have underperformed value stocks during the recent Dow strength:

Since April 19th, value stocks within the S&P 500 have outperformed growth stocks.

Since April 19th, value stocks within the Russell 2000 small cap stocks have outperformed growth stocks.

As the Dow has made new highs, sectors have moved in different directions:

Real estate stocks (IYR) are down more than 5% since March.

Retail stocks (RTH) are down about 3% since March.

Semiconductor stocks (SOX) are down about 4% since March.

Housing stocks (HGX) are down over 8% since March.

Defense stocks (DFX) are up about 5% since March.

Oil stocks (XOI) are up nearly 10% since March.

Gold and silver stocks (XAU) are up over 20% since March.

In short, we've been seeing sector rotation out of growth and into value hard assets as interest rates have risen, energy prices have climbed, and the dollar has declined. The market seems to be betting against the consumer and against a robust economy.

Thursday, May 04, 2006

Narrow Ten Day Closing Range: What It Means

When we divide the sample in half based on closing trading ranges, however, a pattern shows up. When the ten-day range has been narrow (N = 395), the next ten days in SPY have averaged a gain of only .26% (228 up, 167 down). When the ten-day range has been wide (N = 395), the next ten days in SPY have averaged a rise of .95% (260 up, 135 down).

In general, narrow ten-day ranges have led to subnormal returns ten days later.

Wednesday, May 03, 2006

Rumblings Beneath the Market Surface

But it doesn't end there. *Within* the small cap universe since that April date, the value stocks are outperforming the growth issues. And within the mid caps, we're seeing the same dynamic.

In other words, we're seeing a flight to perceived safety: toward blue chips, toward value and away from more volatile, growth-oriented issues.

Might that have something to do with rising interest rates, rising energy prices, and a falling dollar? And might it account for the fact that, on a day where the Dow made a new high, we had 790 stocks making 20-day lows, compared with 930 making new highs? Or that more stocks are below their 7-day moving average than above? Hardly signs of broad strength.

More like a repositioning of assets. And it's not the repositioning you'd expect to see if investors were expecting a vibrant economy.

Methinks tectonic plates are shifting below the market earth.

Tuesday, May 02, 2006

New S&P Highs But Many New Lows: What Up?

Interestingly, when we conduct a median split of the data based on the number of stocks making new 52 week lows, a pattern emerges. When new lows are elevated and the S&P makes a five-day high (N = 260), the next five days average a gain of only .04% (63 up, 67 down). When new lows are restrained and the S&P makes a five-day high (N = 260), the next five days average a gain of .25% (83 up, 47 down).

Clearly, when many stocks are weak and the S&P is making highs, returns are subnormal. I'll be factoring that into decision making in the current market, in which new lows have been especially elevated.

Strong Open After a Weak Close

Monday, May 01, 2006

Flat Market, Rising VIX: What Happens Next?

Since March, 2003 (N = 795), we've had 101 sessions in which SPY has been up or down within a range of .20% from its previous day's close. When the flat SPY day has occurred during a rising VIX (N = 50), the next three days in SPY have averaged a gain of .18% (29 up, 21 down). When the flat SPY day has occurred during a falling VIX (N = 51), the next three days in SPY have averaged a decline of -.12% (22 up, 29 down).

It appears that, in this context, fear--which generates increased option volatility--is more bullish for the market's short-term performance than complacency. Perhaps Mr. Bernanke was doing the market a favor, after all.