Semiconductor stocks ($SOX) have been weak of late, but it's important to take a step back and recognize that these stocks have been weak for years now. Let's go back and retrace the incredible bull and bear run in these issues and see if we might learn something about the dynamics of market bubbles and their bursting.

We start in October, 1996. The SOX is trading in the 180s. Six months later, the SOX had gained 50%, reaching the 290s in February of 1997. By August of that year, the SOX was trading in the 390's--a double within a year's time--before thudding back to earth in the 240s by the end of the year.

By April, 1998, the SOX is back to the 320s, rising about a third in several months' time, before again crashing to the 180s in October of that year.

What we see in the SOX are periods of significant boom and bust that left the average unchanged over a two-year period

and this was before the real boom and bust had occurred! In other words, the prelude to the bubble and the burst of the bubble was significant volatility.

Now the bubble begins in earnest. From October, 1998 to January, 1999 the SOX index doubles in value. A consolidation through May of that year is followed by another 50% spike higher by September, 1999, leaving the SOX in the 570s. Within a year's time, the SOX has tripled in value.

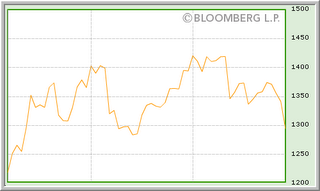

A quick bust in October, 1999 takes about 100 points off the index, but this ground is retraced--and more--by the end of the month. Then, from October, 1999 to March, 2000, the SOX moves steadily higher to an amazing 1362: well over doubling in less than half a year's time. Indeed, in about a year's time, the SOX had almost quadrupled in value.

Now came the bust. Just one month later, in April, 2000, the SOX was down to the 870s, an amazing drop of over a third. The average made it back over 1200 by July of that year--incredible volatility--only to fall back to the 880s later that month and rise back to the 1100s in September. Then, by November, the SOX dropped all the way to 516: more than a 50% drop in just two months. We bounced to the 700s by January, 2001--still significant volatility--but that would prove the index high that year. In the aftermath of 9/11, the SOX declined all the way back to the 340s.

And the eventual market bottom? After a vigorous bounce to the 600s in March, 2002 (still phenomenal volatility), we dropped unceremoniously to the very low 200s in October of that year. With that, we had retraced nearly all gains back to that 1996 beginning.

The SOX bounced nicely after that, hitting 560 in January, 2004. Since then, levels above 500 have been stymied. Most recently, we peaked in the 530s in April, 2006 and are now trading in the 420s.

What the SOX tell us is that, even with the bull market of 2002-present, we are down 2/3 from the market peak in 2000 and down even from that bounce off the September, 2001 lows. While much of the rest of the market has been in bull mode--especially the smaller caps--the SOX (and much of its NASDAQ cohorts) has been unwinding its market bubble.

If the bubble experiences of gold in 1980 and Japan's stock market in the late 1980s are any indication, it could take years to unwind the incredible run in the SOX. Indeed, as hard as it may be to fathom, it may well be that we have not yet seen the ultimate post-bubble lows in many of these stocks.

And the bubble markets of today? We will see them first by their boom-bust volatility; then by their ramping volume and new highs. As we can see from the SOX, however, these remain volatile--and potentially profitable--trading vehicles well after their bull peaks. In their boom-bust behavior, gold (and other metals) and emerging country stocks are certainly candidates.

An important paper by Lee and Swaminathan details the momentum lifecycles of stocks. If you read it carefully, you'll develop a deep appreciation for how booms and busts occur--and how you might locate the next ones.