Monday, August 14, 2006

What Trading Teaches Us About Life

So many life lessons can be culled from trading and the markets:

1) Have a firm stop-loss point for all activities: jobs, relationships, and personal involvements. Successful people are successful because they cut their losing experiences short and ride winning experiences.

2) Diversification works well in life and markets. Multiple, non-correlated sources of fulfillment make it easier to take risks in any one facet of life.

3) In life as in markets, chance truly favors those who are prepared to benefit. Failing to plan truly is planning to fail.

4) Success in trading and life comes from knowing your edge, pressing it when you have the opportunity, and sitting back when that edge is no longer present.

5) Risks and rewards are always proportional. The latter, in life as in markets, requires prudent management of the former.

6) Happiness is the profit we harvest from life. All life's activities should be periodically reviewed for their return on investment.

7) Embrace change: With volatility comes opportunity, as well as danger.

8) All trends and cycles come to an end. Who anticipates the future, profits.

9) The worst decisions, in life and markets, come from extremes: overconfidence and a lack of confidence.

10) A formula for success in life and finance: never hold an investment that you would not be willing to purchase afresh today.

Sunday, August 13, 2006

Trader Performance: What Contributes to Profitability?

Part of the performance equation is continuous learning; turning ordinary experience into a platform for self-improvement. Part of it, too, is working on oneself and cultivating our ability to exploit edges in the marketplace and sustain our intentions. Many different problems can interfere with performance--trading woes as well as emotional ones--but hard work on these is not enough; we need to structure our development in the right ways. I've learned quite a bit from observing successful traders, including--alas--how fleeting that success can be if the trader's development process is not ongoing.

My return to regular trading in the past two months has provided a very hands-on sense for what contributes to performance. I started out a bit shaky, but have since maintained solid profitability. If I'm honest with myself, I have to say that I haven't really become better at making money. Rather, I've become better at not losing it. And I think that's an important distinction.

The chief factor that impacts my profitability, I believe, is my selectivity. There are some days--I can feel it!--when I sit down at the trade station and I'm eager to trade. Other days, I seem to hit that Zen place where I can let the trades come to me. It's like that line in Reminiscences of a Stock Operator: it's not the trading that's makes you money; it's the sitting. When I don't *need* to trade and stay selective, it's as if I allow a different part of my brain to synthesize all the research I've done and all the market action I'm seeing. Out of that synthesis, I get to the point where I truly *see* a trade developing. And I jump on board.

Here's the great dilemma of performance: It takes a phenomenal act of will to develop ourselves and become elite performers--and yet, at the moment of actual performance, we cannot will ourselves to win. The very act of trying to win--attempting to force victory--interferes with performance itself and our ability to access all of our accumulated experience. It takes, for example, considerable will to practice one hundred free throws at each basketball practice. The act of making a clutch free throw during an actual game, however, has to come effortlessly. Aim the ball--try to invoke will--and all you'll hear the the clunk of the ball against the rim.

So what is the key to performance success? Perhaps this: the ability to let go of will after having cultivated it throughout preparation. After so much effort pursuing success, the gold ring goes to those who allow success to find them.

Saturday, August 12, 2006

Trading With the NYSE TICK - Part Three

For this study, I use the Adjusted TICK statistic reported daily on the Trading Psychology Weblog. This is a daily average of the moment-to-moment TICK readings, adjusted to create a zero mean. As a result, positive numbers mean that there has been net buying sentiment on the day; negative numbers indicate the reverse. The correlation between this daily Adjusted TICK reading and daily price change in SPY has been over .70, suggesting that about half of all variance in price can be attributed to trader activity at the bid vs. offer across the universe of NYSE stocks.

Since July, 2003 (N = 774 trading days), I found 63 occasions in which the S&P 500 Index (SPY) was up by more than 1% on the day. Four days later, SPY was up on average by .07% (35 up, 28 down). That represents no bullish edge whatsoever relative to the average four-day SPY gain of .14% (432 up, 342 down) for the entire sample.

Now, however, let's factor the NYSE TICK into the mix. When SPY has been up by more than 1% *and* the NYSE TICK has been strong (N = 31), the next four days in SPY average a gain of .39% (22 up, 9 down). When SPY has been up by more than 1% and the TICK has been weak (N = 32), the next four days in SPY have averaged a loss of -.24% (13 up, 19 down). Clearly, the TICK makes a difference: a single day's TICK reading has bullish or bearish implications four days out.

How about when the S&P 500 (SPY) is weak on the day? We had 67 occasions in which SPY has been down by more than 1% in a single day since July, 2003. When the SPY was weak and the NYSE TICK was relatively strong (N = 34), the next four days in SPY average a gain of .39% (21 up, 13 down). When SPY was weak *and* the TICK was weak (N = 33), the next four days in SPY averaged a gain of only .03% (16 up, 17 down). Once again, we see that a single day's TICK reading exerts an influence several days out.

Now let's look at the TICK over multiple days. When the adjusted NYSE TICK averages more than +500 over a four-day period (N = 36), the *next* four days in SPY average a gain of .39% (23 up, 13 down). That is much stronger than the average four-day gain of .14%, as noted above. When the TICK averages less than -500 over a four-day period (N = 34), the next four days in SPY average a gain of .48% (23 up, 11 down)--again much stronger than average.

What we see is that very positive trader sentiment over a several day period tends to generate strength over the next several days, but very negative sentiment tends to lead to reversals. The bottom line is that the moment-to-moment lifting of offers and hitting of bids among traders does make a difference--even on a multi-day time frame.

Friday, August 11, 2006

Trading With the NYSE TICK - Part Two

In my last post, I suggested that the NYSE TICK was an effective short-term measure of sentiment and illustrated a common trading setup utilizing the TICK. In this post, I'll show you an application of the TICK that you're unlikely to have encountered anywhere else.

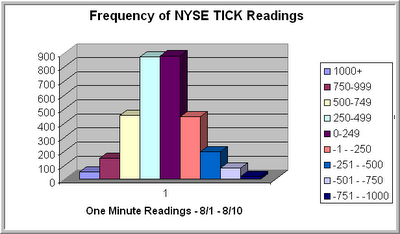

The chart above displays the frequency of closing one-minute NYSE TICK readings for the past eight sessions. I used eight sessions as my lookback period, because the S&P 500 Index has been relatively flat during that period. What that tells me is that this distribution of TICK values (i.e., this distribution of trader short-term sentiment) has been associated with a relatively trendless S&P market.

Note that the median TICK value in the sample is not zero; it is +237. We also tend to have fatter tails on the positive side of the TICK than the negative. (Not shown on the chart are two data points below -1000).

Now how can we use this information to determine the psychology of the market?

My research suggests that, if the relatively flat trading action of the past eight sessions is going to transition to a trending market, we will need to see a shift in the distribution of NYSE TICK values. Such a shift indicates that either buyers are more aggressive in taking offers or in hitting bids. By comparing the distribution of today's TICK readings to the recent distribution, we conduct a running assessment of trader sentiment and whether it is bullish (more positively weighted than the past eight days), bearish (more negatively weighted than the past eight days), or neutral (similar to the past eight days).

It is the distribution of TICK values--and not any single reading in itself--that is significant, indicating shifts in trader sentiment. The beauty of the indicator is that it measures sentiment via trader actions, not their stated beliefs. By viewing TICK distributions in relative terms--comparing today's market to recent markets--we can learn more about those shifts in trader sentiment than we can by focusing on the absolute value of the TICK readings.

A quick and dirty way of accomplishing this is to subtract the median value of the TICK for the lookback period (+237) from each closing one-minute value. If this Adjusted TICK, when cumulated, creates a positive sloping line, you know you have net relative positive sentiment. If the summed values of the Adjusted TICK create a negatively sloping line, you know you have relatively bearish sentiment.

Composite NYSE TICK readings (adjusted for recent lookback periods) are summarized daily on the Trading Psychology Weblog. (Note: the Weblog measure uses 10 second readings of the TICK, not one-minute values). In the third post in this series, I will show how these composite readings make the TICK relevant and useful for longer timeframe traders. The best indicators, I find, are ones that tap into the psychology of the marketplace itself.

Thursday, August 10, 2006

Trading With the NYSE TICK

Here's a screen shot from my trade station. It's a little tough to see (click chart for better view), but the red candlesticks are the ES futures, the blue bars are the NYSE TICK, and the yellow bars are ES volume. Everything is in 2-minute increments.

The NYSE TICK tells us how many stocks are trading at their offer price minus those trading at their bid, and the figure is updated several times per minute.

It is a great measure of very short-term sentiment, because it captures the degree to which the broad market reflects aggressiveness of bulls (lifting offers) vs. bears (hitting bids).

Notice above that we make a low with the NYSE TICK dipping to the -600 region (first red arrow pointing up). At subsequent lows, we get higher negative readings in the TICK (next two red arrows). What is happening is that traders are less aggressive in hitting bids during that period. Moreover, volume in the ES is drying up with the selling.

That emboldens the bulls, who begin to lift offers and create an upside breakout in the TICK on increased volume. Catching that development was good for an excellent short-term trade. This setup occurs with daily regularity, as momentum swings from bears to bulls and back again.

Double Outside Days: What Happens Next?

Going back to 1996 (N = 2637 trading days), I could only find 8 examples of back-to-back outside days in SPY. Three days after the double outside days, the market was up 6 times, down 2, for an average gain of 1.33%. That's much stronger than the average three-day gain of .11% for the entire sample. While this is too small a group of occurrences to stand on statistically, it's clear that bulls have tended to win the tug of war in the past when we've had double outside days.

Overall since 1996, we've had 286 outside days in SPY. Interestingly, on the next day, SPY has been down on average -.03% (155 up, 131 down), certainly no edge relative to the overall sample. By three days out, however, SPY is up on average by .23% (171 up, 115 down), which is again stronger than the average three-day change for the entire sample (.11%; 1431 up, 1206 down).

Perhaps the most relevant and interesting finding is that, when the market is down after an outside day (N = 131), the drop tends to be reversed in a majority of instances over the next several days. Four days later, for instance, SPY is up by an average of .66% (81 up, 50 down), which is stronger than the market's average four-day gain of .14% (1441 up, 1196 down).

In short, double outside days are rare, but have tended to lead to bullish outcomes. Outside days have tended to be bullish several days out and particularly if the day after an outside day is down. The market is steeply lower overnight as I write this and we've broken below an intermediate-term trading range, as the Weblog noted last night. Let's see if the breakout pattern overwhelms the outside day pattern.

Wednesday, August 09, 2006

When the U.S. and EAFE Markets Move Together

Interestingly, when the U.S. and EAFE are highly correlated on a 10-day basis (.925 or greater; N = 84), the next 10 days in SPY average a gain of .87% (58 up, 26 down). This is stronger than the average 10-day gain of .53% (520 up, 339 down).

Conversely, when the U.S. and EAFE are loosely correlated on a 10-day basis (.50 or less; N = 92), the next ten days in SPY average a gain of only .19% (53 up, 39 down).

When the S&P has risen 2% or more in a 10-day period (N = 186), the next 10 days in SPY have averaged a gain of .41% (112 up, 74 down). When the correlation between the U.S. and EAFE has been above average, however (N = 93), the average 10-day gain has been only .25% (52 up, 41 down). When the correlation between the U.S. and EAFE has been below average (N = 93), the average 10-day gain has been stronger at .58% (60 up, 33 down).

What this suggests is that a world that moves in lockstep may have very different implications for future price change than a world that moves in separate directions. Moreover, this relationship appears to be different under bull and bear conditions. This is an area for fruitful research, I suspect.

Tuesday, August 08, 2006

Cumulative Demand/Supply Index: The Case for the Bears

On Friday and Monday, we hit 50 on the Cumulative DSI Line, which is very overbought. When that has occurred (N = 30) since 2003 (N = 871 trading days), the next 10 days in SPY have averaged a loss of -1.34% (5 up, 25 down). That is a huge bearish edge, relative to the average 10-day performance of SPY (up .46%; 514 up, 357 down) for the entire sample.

In my last post, I found a bullish intermediate-term edge associated with the TRIN. Here I find quite a bearish edge. I post this because it is typical of the messiness associated with markets and historical analyses. It is the preponderance of evidence--not the results of any single analysis--that should drive trading and investment decisions.

When Investors Don't Believe a Market Rise: High TRIN, High Price

I went back to the beginning of 1990 to see how common this was (N = 4171 trading days). Since then, we've had 440 occasions in which 10 or more days out of 15 have had TRIN values above 1.0. This tends to occur in declining markets, as you might imagine: the average 15-day price change in the S&P 500 cash index is -2.58%. Fifteen days later, the S&P is down by an average -.14% (223 up, 217 down). That is much weaker than the average 15-day gain of .53% (2444 up, 1727 down) for the entire sample. In other words, when volume has been concentrated in declining issues over a three-week (15-day) period, the next three weeks have tended to underperform on a historical basis.

Interestingly, however, we've had 53 occasions in which there have been 10 or more days in a 15-day period with a TRIN above 1.0, but the S&P 500 Index has been *up* by more than 1% (similar to the current market). Fifteen days later, the S&P was up on average by .66% (32 up, 21 down). And when the S&P was up by more than 2% during a high TRIN 15-day period (N = 29), the market was up 15 days later by an average of 1.52% (22 up, 7 down)--quite an outperformance.

Think of it this way: When investors don't believe a rise, they continue selling the most liquid, high-volume stocks. This creates a situation in which TRIN is high, but price is up. If their selling cannot bring the market down, on average the market tends to go higher. It's when those investors are all buying the most liquid shares, driving TRIN down, that we have greater worries regarding a reversal. I will be watching carefully to see if this pattern plays out in the wake of the Fed meeting.

Monday, August 07, 2006

The Best Psychological Test of All

But how can we know if we're truly operating in our ideal niches, whether in trading, romance, or careers? It turns out that there is a very simple psychological test that can provide this information.

Keep a journal of your emotional experience: how you are feeling at the end of your mornings, afternoons, and evenings. Make particular note of the number of occasions in which you were totally absorbed in what you were doing--so much so that you lost your sense of time passing and lost your awareness of yourself. Also make note of occasions in which you felt frustrated for any reason.

The result of your psychological test is simply the ratio of occasions in which you are absorbed to occasions in which you are frustrated. It turns out that highly creative, productive, and successful individuals have an unusually high ratio.

The reason for this is that these successful people are operating at that nexus of interests, talents, and skills. Because they're doing what they love and have the resources to do it well, they become wholly absorbed in their experience. This is the "flow" state described by Mihalyi Csikszentmihalyi: a pleasurable, altered state of consciousness, in which we feel at one with our situation.

During frustration, on the other hand, we are either doing something that doesn't interest us or something for which our skills and talents are poorly matched for the demands of the task. If task demands are too easy, we become frustrated with boredom. If task demands are excessive, we become frustrated by our inadequacies. Frustration divides subject and object; in flow, those are joined. It's the difference between a highly satisfying sexual experience and a highly unsatisfying one.

If you're operating in your proper niche, you will be experiencing a state of flow on a regular basis. You will be doing what you do well, and you will love and value what you're doing. That is true for the job you're in, the marriage you're in, and the trades you're in. That psychological test applies to most of life's arenas.

Too often, we justify frustration today by the vague hope of fulfillment tomorrow. In my book, I mentioned the Kansas bar near my home where a neon sign promised "Free Beer Tomorrow". Of course, naive patrons who returned the next day were always told that the free beer was, indeed, tomorrow.

In the end, life is a succession of situations: careers you're in, people you know, relationships you enter, markets you trade. You are your situation: you always experience the fit--or lack of fit--between who you are and what you're doing. Successful people find good fits in life: their situations bring flow. Taking your emotional temperature at the end of trading days--assessing your periods of flow and frustration--will tell you a great deal as to whether or not you're in the right markets, with the right methods, in the right timeframes, with the right skills.

Don't settle.

Sunday, August 06, 2006

Discipline and Devotion

A good deal of the advice dispensed by trading coaches and psychologists addresses this discipline problem.

But what if the lack of discipline is not a problem? What if we view departures from trading plans and intentions as *information*, not as weakness? As it turns out, those departures can be quite informative.

You see, we naturally gravitate toward the nexus of our values (interests), talents (native abilities), and skills (acquired competencies). On average, we tend to enjoy doing what we're good at and we tend to build skills when there is a foundation of talents to support them. The artist who spends long hours at the canvas doesn't have to draw upon "discipline" to sustain an interest in painting. The hard work is hard play: the discipline stems from a devotion to a craft--and to the ability of that craft to crystallize the artists' interests, talents, and skills.

My son Macrae labors over writing assignments in school. It takes quite a bit of discipline to get the work done. It's not where his interests, talents, and skills are conjoined. He will focus on video games, however, for hours at a time and master a new game in a single day. The action of the game story line, combined with the demand for quick response and rapid recognition, create a kind of devotion that makes discipline unnecessary.

When we veer from our market discipline, there's an important piece of information in that. Our trading style (or maybe even trading in general) is more like my son's writing than his video gaming. If we pursue a market and a trading style that truly capture our interests and exercise our talents and skills, we will be as absorbed in what we do as the artist or gamer. The lack of devotion--and our need to invoke discipline as motivation--informs us that we are not doing what we are meant to be doing.

My favorite example of this occurred when I first tried to trade on a full-time basis. I stayed in touch with other traders by IM and soon found myself spending more time interacting with them (and helping them with their trading) than following the market myself. Incredibly, I missed quite a few good trades because of the volume of my messaging.

Was my "lack of discipline" a weakness? No! It reflected my strengths. I'm a psychologist for a reason: that's where my values, talents, and skills come together. We will always gravitate toward what *means* the most to us--and many times that will take us away from the things we tell ourselves we *should* be doing. The answer is not more discipline; it's to pursue our devotion.

There's something on this Earth you're meant to do and, when you find it, you won't need discipline to make you pursue it. The greats, to paraphrase Ed Seykota, don't have talents; the talents have them. If you're veering from your path, figure out what you're heading toward. You may just find your passion.

Saturday, August 05, 2006

Signs of a Risk-Averse Market

If we just look at the S&P 500, we see that 43 stocks made new 52-week highs, against 6 new lows. Among the NASDAQ 100 issues, 7 made new highs and 1 made a new low.

Fully three-quarters of all S&P energy stocks are trading above their 50-day moving averages, and over 50% of all S&P 500 stocks. Alas, only about a third of NASDAQ issues are displaying comparable strength.

But it's not just the NASDAQ. Signs of a risk averse market abound. The top four performing sectors, according to Barchart, are gold, silver, soft drink/beverages, and copper. According to Decision Point, the top three Rydex sector funds in terms of assets are Energy Services (228.3 million), Precious Metals (209.7 million), and Energy (175.3 million). No other sector reaches 100 million dollars in assets. Technology? It's down to 16.8 million. Internet? 3.9 million.

The ratio of Rydex bear fund assets plus money market assets to bull market assets is 1.09, in Decision Point's latest tally. Traders are not pouring money into Energy Services, Precious Metals, and Energy because they love stocks. They are making big bets on Dollar Armageddon, just as daytraders back in the day made big bets on the Internet.

In such an environment, big is better because it's perceived as safer. Of stocks trading above $10 a share, 289 made new 52-week highs on Friday and only 49 new lows. But stocks trading under $10? 19 new 52-week highs and 78 new lows. The percentage of S&P 600 small-cap stocks trading above their 50-day moving averages has lagged that of the large cap S&P stocks since May--as has the small-cap advance-decline line vs. that of the large caps.

During the early part of the recent bull market, small and midcap stocks led the way up. That is no longer the case. Value stocks among the S&P 500 have recently trounced growth issues, and value funds in the Rydex attract far more assets than growth. It's a risk-averse mentality, and it's one of the few things keeping my own bearishness in check. If there's one truism in finance, it's that markets do not reward systematic risk aversion.

Friday, August 04, 2006

Seeing The Gorillas in the Middle of the Market

The point is that the brain is a kind of search engine: a Googler of reality. If we program our search to look for passes among basketball players, that's the output we receive from the brain. What is extraneous to our search (gorillas) is eliminated. When we conduct a broad search, we receive a wider range of outputs. Focused searches work well if we're looking for a specific item, such as lost car keys. They don't work so well when we need to process all of the information needed to survive in an environment of risk and uncertainty.

It is very easy to approach the markets in focused search mode. We develop a hypothesis about the market (bullish or bearish) and we prime ourselves to look for certain chart patterns or indicator readings. In our haste to find what we're looking for, we can miss the gorillas in the middle of the market. Afterwords, we might look back on market action and think, "How in the *&#@ could I have missed that??!!"

Gonzales writes, "The practice of Zen teaches that it is impossible to add anything more to a cup that is already full. If you pour in more tea, it simply spills over and is wasted. The same is true of the mind. A closed attitude, an attitude that says, 'I already know', may cause you to miss important information. Zen teaches openness. Survival instructors refer to that quality of openness as 'humility'. In my experience, elite performers, such as high-angle rescue professionals, who risk their lives to save others, have an exceptional balance of boldness and humility..." (p. 91).

There is a concise formula for trading success: boldness and humility. The boldness to act on what you see with the conviction, and the humility to realize that what you see may not be all that is there.

Notice how so many of the excellent market bloggers--Charles Kirk and Trader Mike come readily to mind--track a variety of sectors and indices, examining the market from multiple angles. They're not just looking for the passes on the basketball court; they want to make sure they're not missing any gorillas in the picture.

It's those gorillas in the middle of the market that we don't see that can catch us when we're lacking Gonzales' humility.

Oh, and by the way, did you know that, in yesterday's market, 917 stocks trading above $10 a share made 20-day highs and only 258 made new lows? But, among stocks trading under $10 a share, 199 made new 20-day highs and 241 made new lows.

How easy it is to miss those gorillas.

Thursday, August 03, 2006

Thursday Update: Waning Market Momentum

The pattern of fewer stocks making new highs has been going on for a while now. Among the S&P 500 stocks, we had 92 new 52-week highs in March, 75 in May, and only 27 during today's trade. The pattern is the same among the S&P 600 small caps: 100 new highs in April, 80 in May, and only 24 on Thursday. Markets lose strength before they gain weakness; until this pattern changes, I view the action since March as part of a broad topping process, with May as a candidate high for the bull market.

Becoming an Agent of Continuous Learning

Much of my morning routine before the market open consists of looking at what has made the recent market distinctive. Perhaps it's an extreme indicator reading or an unusual pattern of price change. Whatever that distinctive element is, I then look back in market history to see what has characteristically occurred following that event. That, many times, gives me a clue for the market's overall direction during the coming day. I then track volume flows trade by trade and minute by minute (as outlined in my recent post) to see if large traders are indeed trading in the direction anticipated by my historical study. When those factors--historical tendency and reading of the tape--are in line, that is when I will take a trade.

My performance, as a result boils down to three elements:

- Strategy - aligning my trade with historical odds;

- Tactics - aligning my trade with volume flows for the day;

- Execution - using a reading of large trader behavior to obtain good prices on entry and exit and using position sizing and stops to ensure that I take equal, moderate risk on all trades.

Breaking down my performance that way allows me to more readily see where I have gone wrong in trading and what I'm doing right. I've recently hit personal equity curve highs, and it is amazing how much of this profitability has been determined by #3. Your particular strategy (source of overall market edge), tactics (ways of exploiting that edge from day to day), and execution (position management) may be much different from mine, but breaking down your performance into these categories may help you see your strengths as a trader (so you can maximize them) and your weaknesses.

Military units conduct after-action reviews to identify what went right and wrong with a recently completed mission. Coaches will review game tapes with players to work on strengths and weaknesses. Traders can do the same by grading themselves on strategy, tactics, and execution. It's part of becoming an agent of continuous learning.

Wednesday, August 02, 2006

Reading the Market: More on What Every Short-Term Trader Should Know

Imagine the market oscillating from moment to moment. It trades a number of contracts at the bid price, then several at the offer, then more at the bid, and yet more at the offer. This is happening from second to second as you focus on the order book and what is actually trading. What is actually trading is different from the bids and offers in the book, which may or may not actually trade, given the frequency with which large traders will pull their bids and offers before they are hit.

So we want to focus on what is real. What is real is what trades and *where* it is trading. Second to second, it is trading alternately at the bid and offer.

When a large trader lifts 500 from the book (i.e., purchases 500 contracts at the market's offer price), that, in the context of the moment-to-moment market, is a breakout trade. The only reason for buyers to take the offer price is if they think the market's oscillation is going to end and we will find a new, higher bid-offer range.

In that very short-term context, every buyer at the offer and seller at the bid is a breakout trader. The degree to which the market is trending at this shortest timeframe is reflected by the ease with which these breakout traders get paid out. In a rising market, the purchaser of 500 contracts at the market will find other demand coming in to support the price and the market will move higher.

If a large trader lifts an offer or hits a bid and doesn't get paid out, by definition his or her order was not sufficient to budge the market from its oscillation range. (And, of course, if the large trader' s position goes more than a tick in the red, the market is trending against that trader).

Yesterday AM, I had two points of profit in a short trade. The market had already made a nice down move and suddenly a seller hit the bid with 1500 contracts. I knew from experience that, on average, large size hitting bids after sizable down moves have already occurred often provides liquidity for smart buyers who perceive short-term value in the market. When the market did not immediately go lower in the face of that large trade, I took my profit and avoided a nasty run upward shortly thereafter.

If the market could easily absorb a large sell order after having moved steadily lower on orders that were no larger, that told me that we were nearing an equilibrium point. If the large trader is not getting paid out, the market is not trending on the shortest time frame.

This is not theory. This is not hammer and shooting star chart patterns, Fibonacci retracement numbers, wave sequences, oscillator readings, news events, statistical models, or monetary/economic conditions. This is simply how the market is trading and the ebb and flow of supply and demand in the marketplace.

When you combine historical market tendencies (such as those researched on this blog) with a keen reading of real-time supply and demand shifts, it is indeed possible to generate short-term edges in the market. The key is watching the market and what is actually happening, not getting lost in theories and what you think should happen.

Tuesday, August 01, 2006

What History Says About the Stock Market's Prospects

The most recent occasion when we saw the market trading similarly was February, 2001. If you recall, the NASDAQ had taken quite a tumble over the previous year, but the large cap Dow stocks had held up well. Over the next two years, however, the Dow fell a grievous 26%.

The largest number of occasions cluster in the 1992-1995 time period--particularly during March-October, 1994. Here, if you recall, the market faced rising interest rates, but the economy did not go into deep recession. The market drop was quite mild and, two years later, we were up by about 50%.

We next see a cluster in January and February of 1981. Sadly, I'm showing my age by remembering that market quite well. It was also a period of high interest rates. We had bounced off a 1980 low, but were headed lower later that year and steadily until August, 1982, when we launched the great bull market. One year after the 1981 period that resembled our current market, we were down about 10%, but two years later we were up by the same amount, thanks to that 1982 lift off.

February, 1973 provides the next cluster of days similar to the current one. It was not a good time in the market, as we bounced off a decline from the 1972 highs, but then fell precipitously into the December, 1974 lows. This was a time of high energy prices, high interest rates, and deep recession. Two years later, the market was down by more than 25%.

February, 1962 is our next correlate. We had the missile scare and market plunge that year, but quickly righted ourself. The market was down about 3% one year later, but up a little over 10% two years afterward.

Next we have our second largest cluster of similar market periods spanning 1953-1954, with the majority of occasions in Feb.-May, 1953. That market had risen sharply off 1949 lows and was showing modestly higher highs and lower lows for over a year. One year later, the market was up about 10% on average, but two years later it was up by about 50%, reflecting the strong growth of the post-war period.

If we lump all the occasions, we can see that the market was up on average by 10.9% one year later and 36.1% two years later. That two-year performance is stronger than the market's average two-year gain of 17.09% covering the entire sample. Clearly, the two periods of real weakness (2001 and 1973) occurred in the context of major economic slowdown, augmented by event shocks (oil, WTC bombing).

Here's the interesting part. If we look *three* years out, all periods similar to the current one were profitable, except for those 2001 and 1973 occasions, which only lost less than 3% at worst. Indeed, the average three-year gain was 72.4%, much stronger than the average three-year gain of 26.3% for the sample overall.

This time may be different, I suppose, but the historical record suggests that buying for the longer run on near-term weakness would not be a bad strategy. Unless you're anticipating a rerun of 1929, 1973, or 2001, buying a three-year up market in which gains have been moderate over the past year is an attractive proposition. I'll post more on this in the Trading Psychology Weblog tonight.

Monday, July 31, 2006

The Sound of Breaking China?

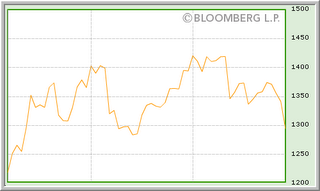

Props to Bloomberg for the chart. We're looking at three months' worth of China's Shanghai (Shenzhen Composite Index) market, and we're looking at multiweek lows.

That, in itself, might not be newsworthy, other than the fact that economists in China are now joining the call for a stronger Yuan. The Yuan has hit its highest level relative to the dollar, a development reportedly supported by the U.S. Treasury Secretary. New IPOs are weighing on the Shanghai market and liquidity concerns abound. So far, China's command economy has not done a good job of obeying commands; the recent response of Shanghai stocks to Yuan strength suggests that, for better or for worse, markets may at last be listening.

Is There a Bias to End-of-Month Trading?

Specifically, I went back to late December, 2002 (N = 903 trading days) and examined returns from the last three days of the month and the first three days of the following month. These six day periods averaged a gain in the S&P 500 Index (SPY) of .15% (156 up, 102 down). That is stronger than the average one-day gain of .04% (494 up, 409 down) for the entire sample.

A look at the 2006 figures suggests that this outperformance has not fallen prey to changing cycles. Since late December, 2005, the average gain in SPY during the last three days of the month and first three days of the next month has averaged .11% (25 up, 17 down). That is stronger than the average one-day gain in SPY of .02% (75 up, 72 down) over that same period.

It does appear that, during the recent bull market, the ends and beginnings of months have been positively tinged. My calculations show that the first three days of the month have been particularly bullish, averaging a gain in SPY of .20% (77 up, 51 down) since 2003.

Sunday, July 30, 2006

Whatever Happened to the Last Hour of Trading?

What does it mean when traders are buying or selling stocks in the last hour of the day? Some have suggested that this might be a "smart money" indicator, in that institutions that want to position themselves for anticipated moves will do so prior to the close to take advantage of overseas strength or weakness. Another way to view trading in the last hour is as a sentiment gauge. Heavy buying (selling) in the last hour means that bulls (bears) are so convinced of their positions that they're not willing to wait until the next day's open to place their orders.

What does it mean when traders are buying or selling stocks in the last hour of the day? Some have suggested that this might be a "smart money" indicator, in that institutions that want to position themselves for anticipated moves will do so prior to the close to take advantage of overseas strength or weakness. Another way to view trading in the last hour is as a sentiment gauge. Heavy buying (selling) in the last hour means that bulls (bears) are so convinced of their positions that they're not willing to wait until the next day's open to place their orders.Yet another view is that buying/selling in the last hour reflects risk-taking (willingness to assume overnight risk), while avoidance of buying/selling reflects risk aversion.

Whatever the explanation, we can see that a cumulative index of price changes in the Dow over the last hour of trading has failed to keep up with the Dow's price advance since the end of 2004. Early in the bull market, traders were buying during the last hour. Since 2005, this has not been the case. Even on Friday and over the past two weeks, when we had a nice pop in the Dow, there was no push to buy in the last hour.

Is smart money avoiding the market? Is sentiment bearish? Are traders behaving in a risk-averse fashion? Perhaps all the above. What we can see for certain is that willingness to step up and buy in the last hour has essentially vanished from this market.