Sunday, December 31, 2006

Trading Psychology and Trader Performance: Selected Posts From 2006, Volume One

* How I use volume flow information in trading to capture the market's psychology;

* Why I find historical analyses of the markets to be useful;

* Reflections on life and the markets;

* Why having odds in your favor doesn't assure success;

* How the S&P 500 Index behaves on a very short time frame;

* Some defining features of market pros I've worked with;

* VIX as a measure of daytrading opportunity;

* A psychology checklist for traders;

* Lessons that traders have taught me;

* Why scalping the stock indices has become so difficult;

* The opening range and market opportunity;

* A solution-focused framework for working on one's trading;

* How the markets confound human nature.

* The most common trading problem of all.

* Why traders lose their discipline.

* Diagnosing trading problems.

* Playing it safe avoids reward as well as risk. Even for investors.

* Living the heroic life: Part one, two, three, four, five

* What a bodybuilder teaches us about life success.

Saturday, December 30, 2006

Interest Rates and the Stock Market: Have Rising Rates Mattered to Traders?

Since that time, we've had 103 occasions in which the rate on the 10-year Note has made 20-day highs. (Observe that this means the Note itself made 20-day price lows). When that has occurred, the S&P 500 Index (SPY) has averaged a gain over the next three weeks of only .07% (56 up, 47 down). Conversely, when the 10-year rates have not made new 20-day highs (N = 626), the next three weeks in SPY have averaged a gain of .54% (389 up, 237 down). It would appear that returns have been subnormal after rates have been rising.

The rate on the 10-year Note has only been above 5% for 67 trading days, and these were clustered during the period of April-July, 2006. Three weeks after these occasions, SPY averaged a decline of -.47% (25 up, 42 down). When rates have been below 4.1% (N = 118), however, the next three weeks in SPY have averaged a gain of .97% (76 up, 42 down). Could it be that the market interprets rates above 5% as potentially damaging to the economy and hence to stocks?

Finally, when 10-year rates have risen by more than 5% in a 20-day period (N = 126), the next three weeks in SPY have averaged a loss of -.20% (53 up, 73 down). When 10-year rates have dropped by more than 5% over the past 20 days (N = 79), the next three weeks in SPY have averaged a gain of .78% (50 up, 29 down). Large rises (declines) in rates appear to have been associated with subnormal (superior) returns in the near term.

Clearly, the recent equity index market has preferred low rates to high ones. The recent rise in rates is one factor that may subdue near-term returns.

Friday, December 29, 2006

What Is Options Sentiment Saying About The Start of 2007?

In my recent posts, I've been analyzing the put/call data for individual equities and for the equity indexes. As I was looking at relative put/call ratios for the equities (how the current ratio compares to the average ratio for a given lookback period), I noticed that we have had quite an elevated relative put/call ratio over the past four trading sessions. In other words, the put/call ratios for the past four sessions have been high (skewed toward puts) relative to the 20-day average ratios.

I decided to take a closer look at four-day elevations in the relative equity put/call ratio going back to 2004 (N = 734). When the put/call ratio for the past four trading sessions is more than 20% greater than its 20-day moving average (N = 62), the next 15 days in the S&P 500 Index (SPY) have averaged a gain of 1.31% (46 up, 16 down), quite a bullish bias. To state it otherwise, when the options traders shift heavily toward put volume over a twenty-day period, the next three weeks in the S&P 500 Index have dramatically outperformed their average. That would bolster the bull case for the start of 2007.

Now for the unexpected finding:

When the relative equity put/call ratio has been 10% or more beneath its 20-day moving average (N = 85), the next 15 days in SPY have averaged a *gain* of .95% (60 up, 25 down), again quite a bullish edge. We are accustomed to thinking of a low put/call ratio as extreme optimism and hence a bearish market indication. It appears, however, that when bullish sentiment shifts strongly over a 20-day period, the shift has bullish implications over the following three weeks.

I will be refining the methods I use to assess relative options movement, so consider this a work in progress. What I hope to determine is whether *changes* in sentiment are more important to market outcomes than absolute levels of sentiment themselves.

Thursday, December 28, 2006

Stock Market Psychology: Equity and Index Put/Call Ratios

Going back to 2004 (N = 748 trading days), I divided the sample in half based upon whether the five-day put/call ratios were relatively low (more bullish) or high (more bearish). I then looked to see how the S&P 500 Index (SPY) behaved over the following five days.

When the five-day equity put/call ratio was relatively low (N = 374), the next four days in SPY averaged a loss of -.03% (190 up, 187 down). When the five-day equity put/call ratio was relatively high (N = 374), the next four days in SPY averaged a gain of .29% (232 up, 142 down). This is quite a difference. It suggests that the common wisdom has held true: market returns are superior when equity options participants are relatively bearish and are subnormal when equity options participants are relatively bullish.

Now let's look at the index put/call ratio. When the five-day index put/call ratio was relatively low (N = 374), the next four days in SPY averaged a gain of .08% (197 up, 177 down). When the five-day index put/call ratio was relatively high (N = 374), the next four days in SPY averaged a gain of .19% (225 up, 149 down). Although the difference is not as dramatic, we see a similar pattern among the index option ratios: when relatively bullish, market returns have underperformed; when relatively bearish, market returns have been superior.

Interestingly, five-day index put/call ratios have correlated with five-day equity ratios by only .05--meaning that they are essentially independent of one another. My best interpretation of the data is that both are measuring sentiment, but among different market participants. The equity put/call ratio is assessing the psychology of speculative traders; the index ratio is tapping the psychology of those using index vehicles for hedging purposes. While there are obviously other uses of the options to be considered, it does appear that the sentiment of these groups is worth tracking for the short-term trader. In my next post, I will examine these ratios on a relative basis (i.e., when they are elevated or depressed relative to their moving averages).

Assessing Stock Market Sentiment: A First Look At Equity and Index Option Indicators

Of course, options are also used for hedging purposes, which could greatly diminish their value as sentiment indicators. A large trader could be selling both puts and calls in anticipation of a flat market, for example.

Despite the hedging caveat, it does appear that equity put/call indicators have value as sentiment measures. Indeed, we may even derive benefit from considering puts and calls as different pieces of information, rather than joining them in a single ratio. My initial look at such relative put ratios and relative call ratios showed some promise as measures of stock market psychology.

To this point, I have focused on the put and call activity of individual stocks (equity puts and calls). With this post, I'll add another data series: the put and call volume for the stock indices. As it turns out, index put/call activity differs greatly from equity put/call data.

One outstanding difference is that the index put/call ratio is skewed toward put volume, whereas the equity ratio is slanted toward calls. Specifically, since 2004 (N = 753 trading days), the average equity put/call ratio has been .73. The average index put/call ratio has been 1.49.

Interestingly, the total volume of equity puts and calls each day since 2004 correlates with the total volume of index puts and calls by a sizable .80. That means that when equity options traders are active in the market, so are index options traders. The daily correlation between the equity and index put/call ratios, however, over that same period has been only .12. In other words, equity and index options traders appear to be responding to the same market events, but they are responding differently.

What this suggests is that the equity put/call ratio may be tapping more into the universe of options speculators and the index put/call ratio may be tapping more into the universe of options hedgers. This might help to account for why the equity ratio is skewed toward calls in a bull market, but the index ratio is skewed toward puts. If this is the case, both might reflect market sentiment, but in different ways--and in ways that might be synergistic. My upcoming posts will explore the value of these indicators.

Wednesday, December 27, 2006

Matching What You Trade With How You Trade

I decided to use a very simple benchmark trading system to evaluate the trading performance of some of the most popular ETFs. On Tuesday, for example, I found 10 ETFs that traded over 3 million shares on the day: QQQQ, SPY, IWM, XLE, OIH, EWJ, XLF, DIA, SMH, and EFA. Notice the growing popularity of small cap trading (IWM) and international trading (EWJ, EFA). Let's see how some of these popular ETFs perform if we simply buy the ETF when it crosses its 20-day moving average to the upside and we sell it when it crosses it to the downside. Such a very simple system should give us a fair number of whipsaw trades, but should also capture nice trending moves.

In the U.S. large caps, of course, we have seen more evidence of mean reversion than trending during the last several years. For example, going back to 2004 (N = 732 trading days), we find that, when the S&P 500 Index (SPY) is above its 5-day moving average *and* above its 20-day moving average (N = 336), the next 10 days in SPY average a loss of -.04% (188 up, 148 down). That is quite an underperformance: The remainder of the occasions in SPY average a 10-day gain of .63% (256 up, 140 down).

Conversely, when SPY has been below its 5-day moving average *and* below its 20-day moving average (N = 194), the next 10 days in SPY average a gain of .77% (124 up, 70 down). A trend following approach in SPY, which would have a trader buying when the index is above its short-term moving averages and selling when the index is below, would have lost considerable money during this bull market.

But with the help of the "performance" feature from the excellent Barchart site, let's actually see how some of the ETFs would have performed since 2005 if we had implemented the simple system described above:

For SPY, we would have had 16 winning trades and 47 losing trades. This would have lost us about 12 SPY points or the equivalent of 120 S&P futures points--during a bull market! The system did catch two large winning trades--it bought in October, 2005 and in July, 2006--but this wasn't enough to make up for a system that had three times as many losing trades as winners.

If we move over to the iShares Emerging Markets ETF (EEM), we find that we had 13 winners since 2005 and 33 losers. Interestingly, however, the system actually made about 25 points over that period. (It started 2005 trading in the 60s). Why? Because the system was able to catch winners that were much larger than the losers. EEM displayed more runs following breaks above and below its moving average than did SPY.

Now let's look at EFA, the iShares MSCI EAFE international ETF. We had 16 winners with our system and 44 losers. That's not at all a favorable ratio, but still the system eked out a little over 5 points of profit. Once again, we saw good sized runs in EFA that simply were not present in SPY--but not ones as pronounced as EEM.

The point of this, of course, is not to trade such a simple system. Indeed, the approach never made more than simple buy-and-hold during the period studied. Rather, we can see that different ETFs display different trending properties that can make the difference between profitability and significant losing. The takeaway message is that *what* you trade should be compatible with *how* you trade.

Tuesday, December 26, 2006

Three Pervasive Myths of Trading Psychology

My work as a trading psychologist has provided me with a fascinating window on the factors that separate successful from unsuccessful traders across a variety of settings, from proprietary firms to investment banks to hedge funds. Having met and worked personally with well over 100 professional traders in the past few years, the main conclusion I’ve come to is that most of the generalizations about trading success are simply not true. In this article, I thought I’d summarize three of the more pervasive myths about trading success out there and offer my own, different perspectives.

Myth #1: Emotions are at the root of trading problems. Yes, emotions can interfere with concentration and performance, but that doesn’t mean that they are a primary cause. Indeed, emotional distress is as often the result of poor trading as the cause. When traders fail to manage risk properly, trading size that is too large for their accounts, they invite outsized emotional responses to their swings in P/L. Similarly, when traders trade untested patterns that possess no objective edge in the marketplace, they are going to lose money over time and experience an understandable degree of emotional frustration. I know many successful traders who are fiercely competitive and highly emotional. I also know many successful traders who are highly analytical and not at all emotional. Trading is a performance field, no less than athletics or the performing arts. Success is a function of talents (inborn abilities) and skills (acquired competencies). No amount of emotional self-control can turn a person into a successful musician, football player, or trader. Once individuals possess the requisite talents and skills for success, however, then psychological factors become important. Psychology dictates how consistent you are with the skills and talents you have; it cannot replace those skills and talents.

Myth #2: Anyone, with dedicated effort, can get to the point of trading for a living. That is nonsense. How many people make their living from acting or musical performance? What proportion of people playing sports can actually make their livelihood from athletics? Many people play chess or poker, but how many can sustain a living from it? Quite simply, to make a living from any performance activity means that you are consistently good at what you do. Not everyone has the talent, skill, or drive to be that successful—in any field. Across the many traders I’ve met in various settings, from home-based, independent traders to professional ones in firms, the best predictors of trading success have been the size of the trader’s account and the resources available to the trader. If a person were to make 30% per year on their accounts year after year, they would be among the world’s most successful money managers. Most money managers of mutual funds, hedge funds, and pension funds cannot sustain such performance. If, however, a trader begins with $60,000 of capital, he or she may not be content with $18,000 of profit. This leads the trader to accept huge leverage and court a risk of ruin when an inevitable string of losing trades occurs. Indeed, such excess leverage is a main cause of emotional distress in trading. Take a look at how the Turtles made their money: they learned a trading method, learned to be consistent with that method, and were given enough money by Richard Dennis that they could trade multiple markets with enough size to scale into positions in each. Even with those resources, not all of the Turtle students could succeed. Talent, skill, and opportunity are the ingredients of success, and these are relatively normally distributed in the trading population, just as they are relatively normally distributed in the population at large.

Myth #3: The main cause of trading failure is a loss of discipline. This is a myth perpetuated by “trading coach” and “guru” types that: a) don’t trade themselves and b) have a vested interest in your belief that their services are all that stand between you and success. The main cause of trading failure is a lack of an objective edge in the marketplace, trading random patterns that have never been tested out for success. We would never consider buying a car simply by looking at it. We’d want to research it, test-drive it, and peer under the hood. Amazingly, however, many traders will risk far more money trading patterns that they never research or test-drive. Many times, the reason they stray from those methods is that, intuitively, they realize that those methods are not working. In any performance field, we find a hard-and-fast truth: the great performers spend more time practicing their performances than actually performing. That is just as true for the Broadway actress as for the Olympic athlete. Many traders, however, think that on-the-job training will be enough. Unfortunately, their accounts often don’t survive their learning curves. A well-placed executive within a trading firm confided to me last year that the average time it takes the average trader to blow through their entire account is seven months. That is why brokerage firms are always on the hunt for new customers. It’s not that these traders are all deficient in discipline: they simply haven’t engaged in sufficient practice to figure out the right markets and trading styles for them and to hone their skills. In every other performance field, you can find relatively easy levels of competition: you can join a community theater, play rounds of golf at the par-3 course, or set the challenge level on your chess computer. There is no easy level of competition in trading, however. When you place a trade on a major exchange, you are up against the pros from day one. No wonder it is so difficult to succeed! Discipline is necessary for trading success, but there is much more to success than discipline. It takes concerted practice and the cultivation of skills at reading and acting upon market patterns.

In an ideal world, I wouldn’t have to challenge these myths. You’d be able to obtain very realistic messages about trading success from brokerage firms, vendors, trading gurus, books, and magazines. The reality, however, is that most of these commercial entities have a vested interest in perpetuating a dream that is, in reality, a cruel fantasy: that, without real, sustained effort, anyone can make it big as a trader.

Does that make me a Scrooge during this holiday season, saying “Bah, humbug!” to the aspirations of thousands of traders? I think not. The reason I wrote my most recent book, Enhancing Trader Performance, was to show that there is a common process beneath the development of elite performance in any field. That process involves several components:

Finding a Niche – Identifying a performance field that takes maximum advantage of your skills, talents, and interests;

Deliberative Practice – Rehearsing skills in increasingly realistic settings to prepare for the challenges of actual performance;

Constant Feedback – Intensive review of performance to identify strengths and weaknesses, so that you can capitalize on the former and address the latter.

The successful traders I’ve known have found a market (or set of markets) and a trading style that capitalizes on their abilities. They have been relentless in working on their skills, using videotaping to review markets and performance and using simulators to rehearse under different market conditions. To sustain such effort requires a love of the markets themselves, something not all traders have. Some traders love the action, some love the dream of making money, some love the opportunity to work for themselves—but many don’t love the work itself: the effort of mastering patterns in demand and supply.

Success is possible in trading as it is in any performance field. If anyone tells you, however, that the path to trading success is different than it is for the surgeon or Olympian, you know that you’re hearing a myth. If you choose the path of the elite performer, trading can be wonderfully challenging and rewarding. If trading is not your ideal path for self-development, however, you are far better off finding your passion elsewhere and managing your money prudently. The goal is to develop the best within you, whether that is as a trader or as something else. Your life deserves nothing less.

Monday, December 25, 2006

A Cross-Section of ETF Returns for 2006

Here we see market performance for four ETFs during 2006: the S&P 500 Index (SPY; dark blue line); the MSCI EAFE Index (EFA; red line); the Russell 2000 small cap index (IWM; yellow line); and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (EEM; turquoise line). The ETFs have been adjusted for an equal market price at the start of 2006 to illustrate their relative performance.

Here we see market performance for four ETFs during 2006: the S&P 500 Index (SPY; dark blue line); the MSCI EAFE Index (EFA; red line); the Russell 2000 small cap index (IWM; yellow line); and the MSCI Emerging Markets Index (EEM; turquoise line). The ETFs have been adjusted for an equal market price at the start of 2006 to illustrate their relative performance.Notice that two themes jump out:

1) International ETFs (EFA and EEM) have outperformed the U.S. market ETFs (SPY and IWM);

2) Smaller cap ETFs (EEM and IWM) have outperformed the larger cap ETFs.

What this means is that the large cap U.S. stocks have been the style cube laggards. We tend to think of those U.S. large caps as "the market", but in reality they are but one sector in a much larger global marketplace.

The chart also illustrates an obvious, but oft-neglected truth: Returns are a function of both what markets you're in and when you're in them. Superior returns have gone to those who invested in international markets and smaller cap shares. Note also, however, that had someone bought the emerging markets stocks or U.S. small caps near the May peak, their returns going forward would not have been impressive.

Indeed, one shift along the style cube that may have begun with that May decline is a shift away from the smaller-cap, more speculative world equity sectors toward large cap value stocks, both international and domestic. With the aging of the European and American baby boom cohorts, it would not be surprising to see a growing emphasis on "blue chip" reliability and dividend payment. The current shift away from growth and toward value may not be a short-term phenomenon, especially given the greater volatility of returns from small cap stocks and emerging markets.

From Style Box to Style Cube: The iShares EAFE Indices

In my recent post to the Trader Performance page of my personal site, I suggested that I viewed ETF trading through the lens of a "style cube", rather than the traditional "style box". We have already seen two dimensions of the style cube: large cap-small cap and value-growth. The important third dimension to the cube we might call "domestic-international": investing in the U.S. vs. investing internationally.

To illustrate two of the cube dimensions, I've created the chart above, which tracks the iShares EAFE Value Index ETF (EFV), the iShares EAFE Growth Index ETF (EFG), and the S&P 500 Index ETF (SPY). Prices have been adjusted for equal value at the start of 2005.

Before we examine the chart, however, allow me to comment on the MSCI EAFE Index. EAFE refers to Europe, Australia, Far East. The index consists of companies in the developed world outside the U.S., with liberal weighting of Japan, U.K., and continental Europe. The ETF covering the MSCI EAFE Index itself is EFA, and it has become an increasingly popular investment and trading vehicle. EFV and EFG break down the Index into value and growth components, so that we can see how those market segments perform relative to one another.

At this point in time, we don't really have ETFs developed for the small cap/large cap portions of the EAFE Index. What we do have, however, is the iShares MSCI Emerging Markets ETF (EEM), which represents international markets in the developing world. To the extent that we view the emerging markets as "small cap", we could think of EEM as representing the international-small cap space on the cube and EFA as representing the international-large cap space. Eventually, as Russell Wild points out in his excellent "Dummies" book on Exchange-Traded Funds, we will likely see actual small-cap and large-cap versions of the EAFE Index itself.

So now to the chart. Notice that value has been outperforming growth among the EAFE stocks, similar to what we've seen in the U.S. market. There is, however, quite a gap in performance between both EAFE subindices and the U.S. large cap market. Traders have done better by being in value than growth, but they have especially profited when they've been in international markets vs. the U.S.

The style cube is simply a way of organizing our thinking about equity performance. Which segments of the market represent the greatest opportunity? Which have the greatest flows of funds? Should we weight our portfolios toward international or U.S.? Toward large cap or small? Toward value or toward growth? With ETFs, any individual investor can become a relatively sophisticated money manager.

I would argue, however, that the style cube ETF options will also become increasingly relevant for shorter-term traders, who will provide much of the growing liquidity in ETFs. Traders will be attracted to ETFs that are trending, those that are showing relative strength, and those that have good volatility for intraday moves.

The day of limiting trading to the major indices (SPY or QQQQ) in the U.S. or even to individual U.S. stocks is rapidly coming to an end. Markets are global, and ETFs permit increasingly global participation by the individual trader. That not only includes the equities that make up the style cube, but also the trading and investment options among the growing number of commodity, currency, and fixed income ETFs. I will be covering those in future posts.

Sunday, December 24, 2006

Significant Buying and Selling Days: The Trajectories of Bull and Bear Swings

Well, this isn't the neatest chart I've ever created, but hopefully it will be informative. What we're looking at here is the S&P 500 Index ($SPX) since 2005 plotted against two 20-day moving averages. The first, in green, is the number of significant buying days that occurred within that 20-day period. The second, in red, is the number of significant selling days within the past 20 sessions.

I defined a significant buying day as one in which advancing stocks outnumbered declinining ones on the NYSE by more than 2:1. Similarly, significant selling days represent occasions in which declining stocks have outnumbered advances by more than 2:1. That 2:1 criterion represents more than one standard deviation of strength/weakness in the advance-decline indicator. Fewer than 10% of market days qualify as being significant in their buying or selling. (The total of all significant days--buying and selling--represents roughly 15% of all market occasions).

What the chart illustrates is that there is a common trajectory to bull and bear swings. Let's walk through the phases of bull and bear swings.

As a bull swing matures, the rally becomes more selective and we see fewer significant buying occasions over time (i.e., the green line is dropping, even as the $SPX continues to rise). That is occurring in the present market. The number of significant selling days has not meaningfully expanded over this phase: we're merely seeing less broad-based buying.

The next phase of the market occurs when we see significant selling days interspersed with the muted number of significant buy days. During the early phases of a bull advance, it is common to see the number of significant selling days at zero for a number of days. As the bull swing matures, we see a creep up in the number of significant selling days. By the time the market makes its price peak, we've already had a lift of the significant selling days off of the zero trough.

Once a bear swing takes over the market, the number of significant selling days expands steadily, reaching a peak at or near the market bottom and exceeding the number of significant buying days. Each bear swing we've had in the past several years has had six or more significant selling days out of 20. Note that, overall, significant down days normally occur only about 7% of the time, which translates to 1-2 occasions out of 20. The bear swing represents a cluster of significant selling occasions.

What happens after this cluster is most interesting. We tend to get a flurry of significant buying days, as value-oriented market participants pick up bargains off the recent lows. That leads to a situation in which, temporarily, over a 20-day period, there are *both* a large number of significant buying and selling days. This clustering of significant selling and buying occasions appears to represent the appearance of longer timeframe participants in the market.

From that point, we go back to the initial phase, as the bull swing continues, but with a gradually decreasing number of significant buying days. That is where we're at in the current market. We have not yet seen a meaningful increase in significant selling days.

I've looked over these data going back several decades. The conclusion I am coming to is that it may be worthwhile to separate significant market days from normal, routine ones when analyzing the market. Normal selling days may well scare off traders, but they do not derail a bull swing. Similarly, normal buying days might lead to short-covering, but they do not reverse a bear swing. A "trend" stays in place until longer timeframe participants detect that stocks are trading too far above or below what they deem to be value. Until those participants engage in broad-based buying or selling, a market will tend to continue in its most recent directional movement.

Many trading strategies, over many timeframes, might be developed out of traders' overreactions to normal buying and selling occasions during directional swings. One longer timeframe implication: if we see a market correction that is no more significant in its selling than the last several have been, we can expect the market to resume its upward course. Every correction we've had during 2004-2006 has represented normal selling vis a vis that longer timeframe--not significant selling. An analysis of significant buying and selling weeks and months confirms that perspective.

Saturday, December 23, 2006

Policies For The TraderFeed Blog And My Personal Site

1) I don't do link exchanges. Ever. If you think my sites are worth linking to, that's very nice. I'm not interested in increasing my "exposure" or in selling any services. I'll be more than happy to look over your site and, if I find unique, educational material, I'll be only too happy to link to it from my personal site. I don't expect links in return.

2) I don't accept payments or promotional considerations for mention on my sites. Ever. If you have something worth linking to, I'll gladly link for nothing simply to inform readers. I do link to commercial sites and services that provide unique information to the trading public, but this is not on a compensated basis. I don't link to sites that are largely self-congratulatory and self-aggrandizing.

3) I post essentially all comments to my blog. The only exceptions would be spam and obscene, name-calling, or vulgar posts that do not offer constructive content. The role of comments is to establish dialogue among colleagues. I prefer that personal messages to me be sent by email to me directly rather than posted as blog comments. I welcome constructive criticism and, indeed, learn much from it. If you send a comment that isn't posted the same day, please email me with a heads up. I average well over 100 emails and comments a day and occasionally overlook some.

4) I do not authorize my articles to be republished on other sites without my expressed permission. Respect for copyright is the operative principle here. At present, only one site has permission to republish selected articles from TraderFeed: Seeking Alpha. Once again, anyone wishing to link to my articles is welcome to do so. The appearance of my articles on a site could be construed as an endorsement, and I choose to avoid that perception.

5) I don't provide coaching or commercial services to the trading public. I appreciate requests for my services and am flattered that someone would think of me, but my responsibilities to the trading firms I work for, my own trading, my writing, and my family preclude such involvements. If I can, I'm happy to provide free referrals for professional services.

So there it is. The blog site and my personal site are designed as educational tools only. They are not designed to recommend specific trades or investments; nor are they designed to provide counseling or psychotherapy assistance. My goal is to help traders become their own coaches and mentors. I've appreciated the tremendous support over the past year and wish all readers a wonderful 2007!

iShares S&P 500 Growth (IWV) and Value (IVE) ETFs: Value is the New Growth

The stock market is like a finely crafted symphony: It develops its themes over time, offering endless variations before transitioning to fresh movements. For the investor, as for the concert goer, excess returns result from an appreciation of themes and their shifts.

The theme of the bull market of the late 1990s up to 2000 was one of growth, highlighted by optimism concerning technology and the Internet. A stormy second movement from 2000-2003 brought this theme to a crashing close, ushering in a new theme that has seen new all-time highs in the small-cap and mid-cap indices, but not in the once high-flying NASDAQ market.

Ah, but the current market's theme is a complex one: Even as we've seen the smallest cap stocks stumble since May, the value component of the market has emerged triumphant relative to growth stocks. Above we see the iShares S&P 500 Growth ETF (IVW) charted against the iShares S&P 500 Value ETF (IVE). Somewhat perversely--and in a complete reversal of the growth bias of the late 1990s--value has become the new growth.

The market is a fine composer: It does not introduce and then toss away its themes. Shifts along the "style box" represent reallocations of capital that don't fade away within days or weeks. Increasingly, with an expanding universe of ETFs, individual investors can track and participate in these shifts.

So what do we call a current theme that sees all-time new highs in the Dow Jones Industrials, outperformance of value over growth, and underperformance of technology? The word "defensive" comes to mind: this bull market is the anti-Nineties.

Friday, December 22, 2006

Why This Editorial and Why Now?

Why is the CIA redacting a routine op-ed piece for the New York Times? From what the Times is saying, even the CIA is acknowledging that state secrets were not the issue in the censoring of the material. The gist of the censored editorial is that the U.S. has not been sincere in pursuing dialogue with Iran. What is unusual is that the authors have written on this topic over the past several years, with no interference from government censors. See, for example, the references linked by the Truthout site, including this one from the Washington Post and this lengthy analysis by the lead author.

Given that no New York Times editorials have been subjected to similar censorship, the question becomes: Why this editorial and why now?

Could it be a misguided effort to not scuttle a tenuous UN agreement regarding sanctions against Iran?

Could it be a PR effort to keep Tehran on the hot seat in the face of a Democratic electoral victory in the U.S. and widespread disenchantment with our involvement in Iraq?

Or could this be a way to minimize dissent ahead of a military build up in the Middle East?

Whatever the motivation, it was deemed important enough by the White House to impose what appears to be a kind of censorship normally associated with strong-arm dictatorships. Let's see if there's another side to this story.

But if this is, indeed, part of an effort to keep public sentiment in favor of a military effort to put Iran on a hot seat, traders in the oil and equity markets might feel some repercussions in 2007.

iShares IWC and IWB ETFs: Tracking the Smallest and Largest Caps

Small capitalization stocks, such as those included in the Russell 2000 Index, have received increasing attention from investors. The iShares IWM ETF, which tracks the Russell 2000 Index, has gone from an average daily volume of a little over 12.6 million shares in 2004 to almost 46.9 million shares during 2006.

Interestingly, however, the corresponding smallest of the small cap funds, the iShares IWC ETF, which tracks the Russell Microcap Index, has averaged only about 76,500 shares per day since its inception in August of 2005. This index captures the smallest 1000 of the Russell 2000 stocks, plus the next smallest 1000 companies. As noted in an earlier article, IWC is a passive index that represents the price behavior of these smallest cap stocks, unlike the PZI ETF, which actively rebalances its microcap holdings. This makes IWC a superior vehicle for studying the market performance of microcaps.

So how does the price behavior of the microcaps differ from that of the largest cap stocks. For the chart above, I chose the corresponding iShares Russell 1000 Index ETF, IWB, for comparison. That index, as its name implies, captures the performance of the 1000 largest companies by market capitalization. This provides a nice basis for comparison since there is no overlap between the stocks in the IWB and IWC products.

Notice that the microcaps (red) have swung more dramatically than the large caps (blue). Indeed, the average daily range of the IWC ETF since its August, 2005 inception has been about 1.2%, considerably larger than the .87% average daily range of IWB over that same period.

The two ETFs tracked one another pretty closely during most of 2005. During early 2006, however, we saw the microcaps dramatically outperform the large caps up to the May high. At that point, with the unwinding of the carry trade and weakness in emerging markets, the microcaps dropped precipitously. Since the July lows, the two ETFs have again tracked each other relatively closely. As a result, however, the large cap IWB has been making multi-year highs, whereas the microcap IWC has yet to exceed its May peak. In fact, though their paths have been different, the net performance of the large caps and microcaps since August, 2005 has been equivalent.

In line with my earlier article on the EEM emerging markets ETF, we might view the relative performance of IWC and IWB as a kind of sentiment measure. When the microcaps are outperforming the large caps, there is positive speculative sentiment in the market, as we saw during the runup to May. Conversely, when investors are bailing out of the microcaps relative to large caps, as occurred this past summer, relative defensive sentiment prevails.

When IWC and IWB are down concurrently, we have a pretty good indication that traders are fleeing equities. Conversely, when we see a concurrent rise in IWC and IWB, we know that traders are more favorably inclined toward stocks. Since the introduction of IWC in August, 2005 (N = 332 trading days), that has been a contrary indicator for the microcaps.

Specifically, when both IWC and IWB have been up over a five-day period (N = 153), the next five days in IWC have averaged a loss of -.31% (67 up, 86 down). When both IWC and IWB have been down over a five-day period (N = 109), the next five days in IWC have averaged a gain of .72% (70 up, 39 down). That's quite a discrepancy, suggesting that the best time to buy the microcaps has been when traders have not been loving stocks.

Thursday, December 21, 2006

Setting Up Trading On An Economic Report Day

Here's what my Market Delta screen looks like this morning prior to the 7:30 AM CT release of GDP and Initial Claims numbers. Then, at 9:00 AM CT, we have Leading Economic Indicators and at 10:00 AM CT, we have the Philly Fed report on manufacturing, which could turn out to be the most important of all if it shows dramatic weakness.

You can see that Wednesday's market established value (the area where most volume is traded) above Tuesday value region. We bounced higher overnight and have pulled back, so I'm now seeing if we can hold the Wednesday lows for a test of the Tuesday/Wednesday highs.

I like to look at the market's trading range(s) prior to economic releases and then after to see if the data have truly brought fresh buying or selling to the market and especially if the market is repricing its assessment of value. I also look at interest rates and the dollar to see if those markets are undergoing significant repricings in the face of the economic data. We are most likely to see trending moves in stocks (i.e., repricings of value) if the global/macro traders are also repricing rates and currencies.

It sounds simplistic, but it's easy to lose sight of: In a rising market, you'll see bouts of selling terminate at successively higher levels. In a falling market, you'll see buying spurts terminate at successively lower levels. When we have buying or selling bursts that end near the termination points of prior bouts of buying/selling, we have a relatively rangebound market. In a market that shows short-term mean reversion, buying when selling peters out at a higher level or selling when buying dries up at a lower level is often a good trading strategy.

On an economic report day, I like the market to show me its response to news and actually *see* where the buying and selling are terminating. That speaks volumes about the market's pricing and repricing of value over time.

Two Applications of Historical Market Patterns

Here are two very recent examples of extensions of historical patterns:

1) Yaser Anwar's recent blog post summarizes the fundamentals for AIG and sees a favorable outlook. By adding a "technical" component to the fundamental analysis--an identification of recent trading patterns in AIG stock--the investor can address the question of whether to wait to get better prices after a three-week runup in the stock.

2) The Dogwood Report drew upon the two-day trading pattern recently mentioned on this site and conducted a test of a related trading strategy. The long-only strategy handily outperformed buy-and-hold, especially in QQQQ over the timeframe tested, which included a major bear market.

I strongly suspect that integrating historical patterns with sound technical trading strategies would yield fruitful results. If there is a technical trader out there who is also writing a blog and would like to collaborate on a post, drop me a line. I welcome the opportunity to explore synergies among different trading approaches.

Wednesday, December 20, 2006

A Context For The Market Open

Good morning, all. Thought I'd post a screen shot of what I watch to prepare for the market open. Notice that my Market Delta screen is set for 10-tick bars, which means that we form a new bar every time there's a ten tick move in ES. This enables me to see how the pre-opening morning trade compares to how we were trading in the afternoon. You can see clearly that we're trading above yesterday's value region (area with the most volume on the left hand Y-axis) and point of control (1434.75). Notice also how buying dried up as we tried to take out yesterday's afternoon highs, pulling us back into the preopening trading range.

My basic strategy for a first trade of the day is to see how we trade in the opening minutes and especially how the NYSE TICK distribution looks and whether or not we're seeing net buying or selling among large traders on the Market Delta chart. Once I get a handle on that, I'll get into the market for a move to break the preopening range. My research from the Weblog tells me to be alert for a consolidation of yesterday's reversal move, so I'm not assuming we're going higher just because we had good afternoon buying yesterday. Indeed, if we get buying that can't push us above yesterday's highs (and the overnight highs), I'd be a seller in the AM.

Have a great trading day--

Brett

SPY and QQQQ: Once It's A Trend, Will It End?

Since 2004 (N = 745 trading days), we've had 233 occasions in which SPY has been up for two consecutive days. Three days later, SPY has averaged a loss of -.02% (119 up, 114 down)--no bullish edge at all. Conversely, across the remaining occasions in the sample, the average three-day gain in SPY has been .16% (301 up, 211 down). It thus appears that, once we have a two-day bullish "trend", market returns have been subnormal.

When we've had two consecutive down days in SPY (N = 146), SPY has averaged a three-day gain of .25% (89 up, 57 down). Over the remaining occasions in the sample, SPY has been up by .07% over a three-day period (331 up, 268 down). Here we see that, once we have a two-day bearish "trend", near-term returns have been superior.

If we look at the NASDAQ 100 Index (QQQQ), a similar pattern appears. When we've had two consecutive up days (N = 219), QQQQ has been down by an average of -.01% over the next three days (118 up, 101 down). Once again, no evident bullish edge. Over the remainder of the occasions in the sample, QQQQ has been up by an average of .12% over the next three days (284 up, 202 down).

But wait! When QQQQ has been down for two consecutive days (N = 159), the next three days in QQQQ have averaged a gain of .07% (83 up, 76 down). Over the remainder of occasions in the sample, the next three days have averaged a gain of .09% (319 up, 267 down).

Interestingly, we see no evidence of a reversal effect for QQQQ after two down days and a relatively modest effect after two down days. In the S&P 500 Index (SPY), there's a more pronounced tendency toward reversal once a two-day "trend" appears.

Might we be able to classify ETFs and individual stocks based on their simple trending or countertrend patterns? Would such patterns provide useful trading guidance? An interesting post from James Altucher's StockPickr site suggests that similar patterns may indeed guide active trading in the NASDAQ 100 stocks. I'll add a twist to the pattern in my next post.

Tuesday, December 19, 2006

Several Lessons From The Day's Trading

1) There's a difference between a good losing trade and a bad losing trade - A good losing trade provides you with information about the market. My initial short position was a good trade, riding the market's weakness in a short-term downtrend. When the trade reversed and took me out with a small loss, that was concrete evidence that buyers were attracted to value below 1430 in the ES. By waiting for the next round of selling in the TICK, I was able to ride this strength for a decent winner when the ES returned to the top of its preopening range. A bad losing trade results from a failure to take all the facts into account. The only information it provides is a heads-up to stay grounded in the market's volume flow before entering a trade. My last trade ignored solid buying in ES, even as the Russell was pulling back. That's not the kind of market weakness that should justify a short position. The large traders were not hitting bids in the most liquid of the indices. By jumping on a trade that had worked for the past two days before checking all the facts, I made a bad losing trade.

2) When You're Wrong, Get Out - When the market reversed against my initial position, I didn't get stubborn. Similarly, after that last trade (the bad losing one) hit my stop, I was out. Had I fought the market tides at those times, I could have been down significant money on the day. In both cases, I knew where I needed to get out and what would make me wrong. It's back to that lesson I mentioned earlier: It's OK to be wrong, but don't dig a hole for yourself that you can't get out of.

3) Stay Flexible - I went into the day session leaning to the short side, but approached the early morning as a range bound situation to keep myself alert to buying possibilities. When the initial trade reversed on me, I was able to reverse to the long side. Research and market information can give you an opinion about the market, but you always want your opinion to be a hypothesis, not a fixed conclusion. "Don't marry your opinions" is another piece of market wisdom that serves us well.

Perhaps the most important lesson of all, however, is to never stop learning and never stop working on your game. I've been trading since the late 1970s in some shape, manner, or form and I still make some boneheaded mistakes. I am just as happy to post the errors as the good trades. There's something to be learned in both.

Thanks to all who have kindly commented online and off re: the session.

Brett

Another December Morning With the Doc

The challenge I find (which doesn't get easier when you're trying to blog and trade at the same time!) is to keep my eyes on everything. For the last two days, I've looked to the Russell to lead and that's made me money. On that last trade today, the Russell certainly did not lead. The support and buying were in the large caps. I was focused too much on what had worked before and did not stay grounded in my bread and butter, making the market's volume--and its distribution--tell the story.

So there you have it. All in all it was a nice opportunity to demonstrate a few things: 1) getting out of trades quickly if the basic idea isn't panning out; 2) taking what the market gives you when you're right; 3) staying flexible and changing positions in the market as the participation in the market shifts; and 4) always using each day's trade to figure out what you've done right and wrong and learn from both. Have a great day; market wrap up tonight on the Weblog and another blog post to follow today.

9:59 AM - OK, that last trade was an admitted longer shot. I was looking for growing weakness in the TICK and didn't get it. I'm not about to let a winning day turn into a loser, so that's it for me unless something really hits me in the eyes. A wrap up will follow.

9:55 AM - Out of that one with a point loser as well.

9:50 AM - Short Russell

9:43 AM - Scratch; don't like how ND and Russell are trading.

9:36 AM - Bought some ES here; tight stop.

9:25 AM - I'm flat, looking for a place to get long if sellers can't do damage to the recent runup. I'll do a blog post later today explaining more about that long trade. Many important market principles touched upon by both my losing trade and the winning one. I'm in a patient mode here. We just got a burst of buying in the TICK, but not a great price response in ES. Not what I wanted to see.

9:17 AM - Took my 3 pts more in a bit I might enter again on breakout above range

9:10 AM - As long as we see a positive shift in the TICK and lifting of offers by big traders above the 29.50 price, my leaning is to test the upper end of the premarket trading range mentioned earlier (1433 area). The initial buying struck me as short covering, but the second burst had some real size to it and was buying Russells and NAZ.

9:05 AM - Long some ES here.

8:57 AM - Buying solidified, taking me out of my short position with a point loss. The TICK has strengthened noticeably, and the ES returned back into their premarket trading range. The last trade in a trend following mode is always going to be a loser; the key is to keep the losses reasonable. Let's see if we can put in a bottom in ES after the rejection of the move down to the 1426 region.

8:47AM - I added some Russells on the recent bounce; my leaning in this situation is to "dance with the one who brung you" and Russell has made me money the last few days on my short trades. Obviously, I want to see this market stay below that trading range mentioned earlier to stick with the short idea. There was definite short-covering going on during the recent bounce, with large traders lifting offers and getting out. So far, however, I'm not seeing broad based buying in the NYSE TICK. If that TICK distribution goes solidly positive, I'll be out of the Russells. They're sensitive to the TICK for obvious reasons.

8:38 AM - We've opened with weakness; over 1000 more declining stocks than advancing; NYSE TICK negative, but not dramatically so; lots of whippy action. NASDAQ and Russell leading the downside, continuing the recent pattern. We've broken the lows in ES, triggering my selling a small Russell position. Volume above average for this time of day, suggesting institutional participation along with the locals and verifying that we're likely to see some volatile trade.

8:22 AM - The dollar and rates have pretty much stabilized following their moves after the PPI news; no big trending action has continued. DAX also remains above its sessions lows. Basically, I'm viewing this market as in a premarket trading range between the 1433.50 and 1428.75 levels. A move above 33.50 could easily trigger some stops and some short covering. I think we'd see some frantic selling if the DAX makes new lows and the stocks fail to hold the 28.75 level. So my job as a short-term trader is to see if I can handicap the odds of a move outside this range and get in at a good enough price to profit. If buying dries up without us breaking the upper range, I'll lean toward selling. If selling dries up without decisively taking out the lower end of the range, I might buy a little for a countertrend move. My leaning is to be patient and let the distribution of volume tell me what the large traders are doing. No need to get whipsawed early in a trading day. Based on the premarket activity, there should be decent movement in the AM and perhaps through the day. Back after the open.

8:00 AM: Ok, we have producer prices up sharply and home sales up as well, with housing permits a tad weaker than expected. Interest rates jumped on the PPI news , with the 10-year rate moving over 4.6% (though off initial highs). The dollar gyrated on the news and is weaker vs. the Euro, though also off its lows. Stocks fell on the news, with the ES getting as low as 1428.75, nearly ten full ES points off its average trading price from yesterday. The short-term trend is definitely down, but I am hesitant to chase lows after we've come so far below the average trading price. My leaning is to let bulls have their turn and see how much genuine buying vs. short covering we get. I'm watching the DAX, which did not make session lows on the economic news. It has led some nice moves in ES the last couple of trading sessions. Back in a few.

7:25 AM: Good morning. Looks like lots is happening on the heels of yesterday's decline. Here is a report from the excellent Barchart service:

Thailand's SET stock index plunged 14.8% today after the Thai government imposed currency controls in order to clamp down on short-term foreign investment and prevent undue strength in its currency. The Thai government announced that foreign investors will only be able to invest 70% of the funds they transfer into Thailand and will only be able to withdraw their cash if the cash is kept in the country for longer than 1 year. Withdrawals of cash that has been in Thailand for less than a year will be subject to a 10% penalty. The move by the Thai government caused concern that other emerging countries might follow suit. Emerging market stocks in general took a hit today and Asian stocks today generally fell 1-2%. However, the Chinese yuan was little changed today and the Chinese stock indexes today closed higher, illustrating that concerns didn't extend into China which already has very restrictive currency controls.

Notice the hit to emerging nation markets, an interesting development in light of my most recent post. We've got housing starts and PPI on the docket in a couple of minutes; back after the numbers to digest everything. Remember: a volatile premarket tends to bring volatile trade in the morning hours. Let's see...

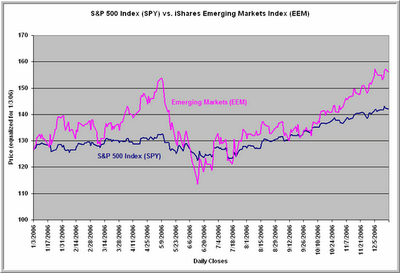

Does The iShares Emerging Market ETF EEM Capture Speculative Sentiment?

The emerging markets have been stellar performers during the 2003-2006 bull market. A harrowing drop in May and June of 2006 notwithstanding, the iShares Emerging Markets Index ETF (EEM) has tripled in value since its debut in May, 2003. By contrast, the S&P 500 Index of large cap U.S. stocks has risen by about 49% during that same time.

What constitutes emerging markets? As the ETF Connect site summarizes, EEM has a relatively even distribution of exposure to various industry groups, with about 17% of the fund in energy; 15% in banks; 13% in materials; 12% in semiconductors; and 12% in telecommunications. South Korea accounts for about 16% of assets; Taiwan for 11%; Brazil, Russia, and China for 10% each; South Africa for 9%; Mexico for 8%; and India for 5%.

The above chart shows that EEM has traded like a very volatile version of the American market. Since 2004, the day to day correlation between EEM and SPY has been .74, but the average daily percentage size move in EEM has been twice that of SPY (1.08% vs. .52%). Even the pattern of changes in EEM has mirrored that in SPY. Since 2004, SPY has gained about 31 index points. 30-1/2 of these points have come during the period between the previous day's close and the next day's open (overnight gap). During the day trading session, SPY has gained only half a point since 2004.

EEM has displayed an even more exaggerated version of this disparity. EEM has gained about 58 index points since 2004. Of those, 104 have come between the previous day's close and the next day's open. During the U.S. daytrading session, EEM has actually lost 46 index points!

All of this has led me to wonder if EEM might be a speculative version of SPY from a trading standpoint. When EEM is outperforming SPY, traders and investors are bullish on this most speculative segment of the world markets. Conversely, when EEM underperforms, traders and investors are avoiding such speculation.

Going back to 2004 (N = 727 trading days), I split the data in half based upon the 20 day relative performance of EEM to SPY. When EEM strongly outperformed SPY (N = 364), the next ten days in SPY averaged a gain of .12% (199 up, 165 down). But when EEM was in the bottom half of its performance relative to SPY (N = 363), the next ten days in SPY averaged a gain of .52% (240 up, 123 down).

What this suggests is that the relative performance of EEM and SPY might be capturing the degree of speculative sentiment in the market. When traders are at their most speculative, the U.S. market tends to underperform compared to those occasions when traders are less risk-taking. Notice that, as during the March-May period, the relative performance of EEM to SPY has been ramping up since October--perhaps a bit of caution for this market.

Monday, December 18, 2006

Three Pieces of Trading Wisdom

1) Focus on being profitable for the week - Individual trades may go against you and individual trading days can offer little opportunity. As a senior trader once explained to me, for the active trader, however, there are enough fresh opportunities in a week to make it reasonable to set a goal of being profitable for the week. You won't reach your goal every single week, but the mere act of setting the goal keeps you focused. For example, you don't want to lose so much money in a single day that you can't make it back during the other days of the week. You also don't want to lose so much money on a single trade that you can't come back during the remainder of the day. When you really push yourself to be profitable every week, you don't let individual days get away from you. And when you don't let individual days get away from you, you start managing each trade carefully to ensure that your largest loss won't exceed your largest gain. Time and again I've seen a consistent sign of progress among developing traders: they stop digging themselves into holes.

2) Take what the market gives you - Today I peeled out of several short positions after a spate of very negative TICK readings in the afternoon. I've learned that such concentrated selling often precedes nasty short-covering rallies. My S&P position hadn't made as much profit as my NASDAQ and Russell positions, but the market doesn't care about that. I took what the market gave me and started the week green. Did the market go down even further after I exited? Absolutely. As one experienced trader explained to me, when the market rewards your position right off the bat, you want to take something off the table. You might let a piece of your position ride if you have a longer-term opinion, but never give green a chance to become red. A winner that turns into a loser is a double loss.

3) Always have something to "lean on" - Scalpers will notice heavy and persistent selling at a certain tick, accompanied by large offers in the order book. They'll lean on that information to find a good entry to sell the market. If the offers disappear from the book or if new buyers start lifting those offers in size, they can get out quickly. Knowing you have something to lean on, however, allows you to ride out the noise between entry and exit. As long as what you're leaning on doesn't vanish, you stay with your idea. Today I leaned on the inability of the Russell to make new highs on Friday. When we got some morning buying, but could not break above the early AM highs (and also above Friday's highs), I added to my shorts and vowed to stay short unless we broke the highs with expanded buying. Leaning on the pattern of Russell weakness enabled me to stick with a good trade idea during a choppy morning.

So let's restate the pieces of wisdom in reverse order:

1) Before you put your capital at risk, have a well-formed trade idea;

2) When your idea pays you out quickly, take some profits;

3) Don't get caught up in individual trades; focus on profitability over a series of trades and days.

I know, I know. These things sound ridiculously simple. But it's only been in the last couple of years that I can look myself in the mirror and say that I'm doing all three consistently. The spinning reverse dunks get the attention in basketball; the long touchdown pass makes the evening replays; and the big winning trades are the ones we like to talk about. The greater part of success, however, boils down to Xs and Os on the basketball court; blocking and tackling on the football field; and following basic fundamentals about framing and managing trades. It may not be sexy to execute on the fundamentals, but it gets the job done day after day and builds a career.

Is A Trending Bull Market Due For A Fall?

I went back to June, 1989 (N = 4326 trading days) and found 337 periods in which the S&P 500 Index was similar to today's market: up by more than 10% over a 100-day period; up by over 5% over the last 50 days; and up by more than 2.5% in the past 25 days, with the gains over 100 days exceeding those of 50 days and those of 50 days exceeding those of 25 days. These have been steady uptrend occasions.

Twenty five days later, the S&P 500 Index was up by an average of only .16% (200 up, 137 down). That is weaker than the average 25-day gain of .90% (2609 up, 1717 down) for the entire sample. When we look 100 days out, however, the average gain following the uptrending period has been an impressive 6.00% (276 up, 61 down). That is stronger than the average 100-day gain of 3.60% (3030 up, 1296 down) for the entire sample.

What we're seeing, of course, is that the market has been highly bullish since 1989--some decent bear moves notwithstanding. After we've already had a trending up move for 100 days, returns have been subnormal over the next 25 days, but have actually been quite healthy over the next 100 days. The reversal effects that we've seen in short-term market movements have not occurred when we look as far out as 100 days.

This has implications for investment--as opposed to active trading--strategies and for traders interested in diversifying their returns by holding over a variety of time frames. About 80% of all uptrending 100-day periods since 1989 have been higher 100 days later. Interestingly, however, seven of the last ten occasions--those since December, 2003--have lost money. Even at the longer time frame, the most recent market regime has not rewarded trend followers.

Sunday, December 17, 2006

Are Money Managers Hedging Their Bets With The ProShares Ultra ETFs?

A unique feature of the Ultra ETFs is that they include separate trading instruments for long and short market exposure. By buying an inverse (short) ETF, a trader makes 2% when the underlying index falls by 1%. The non-inverse (long) Ultra ETF, of course, would rise 2% if the market rises by 1%.

Here are the symbols for the three most liquid Ultra ETFs:

NASDAQ 100: QLD (2x long); QID (2x short)

S&P 500: SSO (2x long); SDS (2x short)

Dow 30: DDM (2x long); DXD (2x short)

My initial idea was to compare volumes for the long vs. short Ultra ETFs to see if they functioned like call volume and put volume among options. In other words, by tracking participation in the Ultra ETFs, we might have a new sentiment indicator.

I'll save that idea for a later date, however. My first look suggested that something else is up with the Ultra ETFs: total volume. But not just all volume: volume in the inverse (short) ETFs. Check it out:

I went back to 7/13/06, which is when I show trading histories for the three Ultra ETFs above (N = 110 trading days). I then compared the average volumes for the ETFs for the first half of the sample and for the second half. Here's what I found:

NASDAQ long (QLD) volume: up 51%

NASDAQ short (QID) volume: up 217%

S&P 500 long (SSO) volume: up 15%

S&P 500 short (SDS) volume: up 69%

Dow 30 long (DDM) volume: down 29%

Dow 30 short (DXD) volume: up 88%

Clearly, we're seeing much more interest in the short product than the long one, an interesting finding in a rising market.

What's more is that this interest is correlated across the Ultra ETFs. I went back to November 1st, which is roughly when we first saw a burst of new volume in the short products, and correlated the daily volumes in the inverse Ultras. The correlation between the NASDAQ inverse volume (QID) and the S&P 500 inverse volume (SDS) was .60. The correlation between the NASDAQ inverse volume (QID) and the Dow inverse volume (DXD) was .87. The correlation between the S&P 500 inverse volume (SDS) and the Dow inverse volume (DXD) was .43. All are healthy, positive correlations. This suggests that when there is buying interest in one inverse ETF, there tends to be buying interest in the others.

Correlations in the daily volume of the long ETFs is also positive and significant: around .50-.60.

What are we to make of the growing interest in the inverse ETFs and the correlated volumes of all six of these Ultra ETFs?

My take is that they are being used as hedging devices by money managers. Many managers who have been buying stocks like banshees this fall have been hedging their bets with these Ultra inverse products. They are getting the best of both worlds: they can say that they participated in the rally and they can extend their stock ownership over longer (capital gains) periods, while at the same time hedging their general market risk.

Over the last five days of relative market strength, volume in the inverse NASDAQ product has exceeded volume in the long product by 5:1. Volume in the inverse S&P ETF has exceeded volume in the long product by over 3:1. There have been no dips in the ratios of short:long volumes in the Ultra ETFs as there have been among equity put/call options.

Bottom line: At least among some money managers, their bullishness may be a mile wide and an inch deep. At the same time they're buying stocks for year end gains, they're making sure their tails are covered. Other managers may be more selective in their bullishness, preferring specific issues, but protecting themselves from overall market risk. In any event, in the Ultra ETFs, we have an interesting tool for examining the behavior of these managers. As the market has broken to new highs, they've stepped up their participation in the inverse ETF market.

Saturday, December 16, 2006

Three Lessons From The Daytraders' Index

Above is a chart of the S&P 500 Index (SPY) since 2004 (red) and an index that I call the Daytraders' Index (blue). The Daytraders' Index consists of the cumulative changes of the market's move from open to close. So, in essence, the Daytraders' Index is a chart of SPY with the effect of the overnight (close to open) action eliminated.

What we can see clearly is that the Daytraders' Index looks very much like a detrended SPY. We are almost exactly at the point in 2006 that we were at the start of 2004, even though SPY is more than 30 points (300 S&P futures points) higher.

There are several important lessons we can gather from the Daytraders' Index:

1) A directional bias in the S&P 500 Index has not helped the daytrader. The daytrader's market has not had a systematic, trending bias, even though we've been in a bull market. The daytraders should not necessarily become more bullish when the S&P 500 Index breaks to new highs, because--in an important sense--that is not the market they are trading.

2) Daytraders need to trade the patterns relevant to their market. Useful historical price patterns may be present in the Daytraders' Index that are obscured by the market's overnight action. Conversely, price patterns over multiple days in the S&P 500 Index may not benefit the daytrader if a large part of the price gains from those patterns occur in the overnight market. Developing an idea from a daily barchart, for example, won't necessarily benefit a daytrader because, even if it is correct, the anticipated movement may not happen at the trader's time frame.

3) The market has been paying a handsome risk premium to traders willing to assume overnight risk. By avoiding overnight exposure, daytraders also insulate themselves from the opportunity of participating in the bull market. Rather than simply grow larger in response to profitability, it could make sense for the daytrader to diversify by time frame and capture some of the market's risk premium. By properly sizing overnight vs. intraday positions, the trader can easily manage the risk of overnight exposure and cultivate a new source of alpha.

In a very real sense, the S&P 500 Index is an amalgam of two different trading markets. One is a relatively trendless day session and the other is a trendy overnight market that responds to international market movements and premarket economic news. In my upcoming posts, I will explore some of the historical patterns in the Daytraders' Index and how they might be relevant to both intraday and swing traders.

Friday, December 15, 2006

Sector Rotation or Breakout Rally: Perspective From The ETFs

Here we see how the different "Spyder" sector ETFs have performed since August. Those that have outperformed the S&P 500 Index (SPY) are coded green; those that have underperformed are in red.

Now here's the interesting thing: Of the seven sectors that have outperformed the S&P500 Index, only one made a new closing high on Thursday. That was XLY, the Consumer Discretionary ETF. The other six sectors that have been strong since August did not make new highs on Thursday.

Conversely, five of the ten sector ETFs that have underperformed the S&P 500 Index closed at new highs on Thursday. My take? The rally Thursday and this AM represent sector rotation and not "the rising tide that lifts all boats". I'm watching carefully to see if this rally broadens out or stalls out. One way of doing that is tracking the ETFs and seeing how many can remain above their Thursday highs. So far, a majority are struggling to ride the tide.

Divergences At The Market Highs: What's Hot, What's Not Among ETFs

When I was putting together today's Weblog entry, I noticed that--even after Thursday's impressive rise--only 1345 stocks across the NYSE, NASDAQ, and American Exchanges had made fresh 20-day highs against 550 new lows. By comparison, on December 5th, we had 1920 new 20-day highs and only 276 new lows.

Above, I take a larger picture from August of this year to the present. The red line is the daily closing price of the S&P 500 Index (SPY). The blue line is the difference between the number of stocks across the three exchanges that are making fresh 65-day highs minus those making 65-day lows. Notice that, recently, as we've moved to new highs in SPY, the net number of stocks making new intermediate-term highs has lagged. (Props to the excellent Barchart site for the new high/low data).

So what's hot and what's not?

Most noticeably, we see that the S&P 500 large cap ETF (SPY) has made a new multi-year high. We see no such new high in the Russell 2000 small cap ETF (IWM) or the NASDAQ 100 Index fund (QQQQ). The midcap ETF (MDY) is knocking at door of new highs, but so far is lagging. In other words, we're seeing divergence based upon capitalization and market.

How about sectors?

I took a look at the 17 State Street "Spyder" ETFs to see which have made new highs since August on this recent rise. Six closed at new highs:

XES - Oil and Gas Equipment and Service

XLE - Energy

XLF - Financial

XLP - Consumer Staples

XLU - Utilities

XLY - Consumer Discretionary

Eleven sector State Street "Spyder" ETFs, however, did not make new highs on Thursday:

XBI - Biotech

XHB - Homebuilders

XLB - Materials

XLI - Industrial

XLK - Technology

XLV - Health Care

XME - Metals and Mining

XOP - Oil and Gas Exploration and Production

XPH - Pharmaceuticals

XRT - Retail

XSD - Semiconductors

While this is a mixed bag, it's clear that, overall, growth sectors are lagging value ones.

They say a rising tide lifts all boats. My research suggests that rising boats are indicative of significant rising tides. On Thursday, there were fewer rising boats than meets the eye.

Thursday, December 14, 2006

Institutional Behavior At The Close: Does It Affect The Next Open?

I went back to 2004 (N = 744 trading days) and divided the sample in half based upon the net buying vs. selling in institutional MOC orders. When there was relatively strong buying at the close (N = 372), the next open in the S&P 500 Index (SPY) was up by an average of .01% (168 up, 204 down). Conversely, when there was relatively weak buying at the close, the next morning's open in SPY was up by an average of .06% (225 up, 147 down). Interestingly, when there was outright net selling at the close (N = 87), the next morning's open was up by an average of .11% (55 up, 32 down).

If you've ever had the feeling that you bail out of positions at the wrong time, at least you now know that you're in good company. Even at the market close, at a very short time frame, we see evidence of reversal effects.

So here's the puzzle: How do we know what institutions are doing at the market close? I'll verify the answer if anyone figures it out and posts it as a blog comment. It's actually pretty simple.