The Demand measure followed by the Trading Psychology Weblog is an index of the number of stocks displaying significant momentum (bullish/bearish) on a short- and intermediate-term basis. After Thursday's rise on the heels of the Fed news, we had the strongest Demand to Supply reading since the bull market began in late 2002.

When Demand has been extraordinarily high (over 160; N = 12) since October, 2002 (N = 942), the market (SPY) has been up by an average of .78% four days later (11 up, 1 down)--much stronger than the average four-day gain of .16% (518 up, 424 down) for the entire sample.

This fits well with my prior research, which suggests that strong and broad upmoves tend to persist in the near term.

Friday, June 30, 2006

Thursday, June 29, 2006

The Dual Road to Trading Success

By collecting hard data on our trading--metrics on the average size, holding time, and number of winning/losing trades; performance under different market conditions, etc.--we work on developing our market edge and we work on our ability to consistently exploit that edge. Knowing what we're doing and how well we're doing it tells us what we're doing right (so we can do more of it) and what we're doing wrong (so we can make improvements). We have patterns of success and we have patterns of failure; the challenge is identifying and understanding these and using them to spur improvement.

"Trading success is a function of possessing a statistical edge in the market and being able to exploit this edge with regularity. Trading failure is most likely to occur when you trade subjective, untested methods that possess no valid edge or when you are incapable of consistently applying edges that are available. Improving your psychology as a trader by itself will not confer an objective edge. Developing or purchasing a valid trading system will not in and of itself make you a great trader. The development of trading methods and the development of yourself as a trader thus must proceed in concert. You are only as good as the methods you implement and your ability to implement the methods."

"Trading success is a function of possessing a statistical edge in the market and being able to exploit this edge with regularity. Trading failure is most likely to occur when you trade subjective, untested methods that possess no valid edge or when you are incapable of consistently applying edges that are available. Improving your psychology as a trader by itself will not confer an objective edge. Developing or purchasing a valid trading system will not in and of itself make you a great trader. The development of trading methods and the development of yourself as a trader thus must proceed in concert. You are only as good as the methods you implement and your ability to implement the methods."

The Psychology of Trading, p. 295

Wednesday, June 28, 2006

A Lesson to be Learned--and Relearned

Charles Kirk a little while back made the useful observation that keeping a journal provides a great resource much later in time when you reacquaint yourself with your own best ideas. The most important trading lessons, such as risk management, are ones that not only have to be learned, but relearned. Our journals and notes can be valuable tools of relearning. Here's one of my own writings that I've revisited lately in pursuit of new research and trading methods:

"A stationary price series is one that is generated by a single process. If cards are drawn at random from a deck in a game of blackjack, the distribution of cards selected will show evidence of stationarity; that is, they will follow a stable, predictable distribution over time.

If, however, the dealer at the casino shifts from using a single deck of cards to using a shoe of several decks, the distribution of cards selected will change. The distribution will now show evidence of nonstationarity--there will be significant differences in the frequency of cards coming up using many decks versus one.

Stationarity is important to traders because every so often the markets switch the number of decks from which they're dealing. The market will meander in a given direction with low volatility for a while and then suddenly zoom off on high volatility. If you look at the statistical distribution of price changes, you can see evidence of nonstationarity...

One of the greatest weaknesses of the methods utilized by many traders I have interviewed is the failure to assess stationarity and factor that into decisions. Instead of identifying the type of market they are in and trading methods specific to that kind of market, they adopt mechanical signals and uniform chart or oscillator patterns to apply to all markets. As long as the market works from the same number of decks, their methods may produce profits. Once the changing cycles described by Niederhoffer change the decks, however, the formerly useful methodologies will produce substandard results.

Any single set of trading rules or methods is vulnerable to breakdown if repeatedly traded across nonstationary periods."

"A stationary price series is one that is generated by a single process. If cards are drawn at random from a deck in a game of blackjack, the distribution of cards selected will show evidence of stationarity; that is, they will follow a stable, predictable distribution over time.

If, however, the dealer at the casino shifts from using a single deck of cards to using a shoe of several decks, the distribution of cards selected will change. The distribution will now show evidence of nonstationarity--there will be significant differences in the frequency of cards coming up using many decks versus one.

Stationarity is important to traders because every so often the markets switch the number of decks from which they're dealing. The market will meander in a given direction with low volatility for a while and then suddenly zoom off on high volatility. If you look at the statistical distribution of price changes, you can see evidence of nonstationarity...

One of the greatest weaknesses of the methods utilized by many traders I have interviewed is the failure to assess stationarity and factor that into decisions. Instead of identifying the type of market they are in and trading methods specific to that kind of market, they adopt mechanical signals and uniform chart or oscillator patterns to apply to all markets. As long as the market works from the same number of decks, their methods may produce profits. Once the changing cycles described by Niederhoffer change the decks, however, the formerly useful methodologies will produce substandard results.

Any single set of trading rules or methods is vulnerable to breakdown if repeatedly traded across nonstationary periods."

From The Psychology of Trading; p. 86-7.

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Top Ten Reasons Traders Lose Their Discipline

Losing discipline is not a trading problem; it is the common result of a number of trading-related problems. Here are the most common sources of loss of discipline, culled from my work with traders:

10) Environmental distractions and boredom cause a lack of focus;

9) Fatigue and mental overload create a loss of concentration;

8) Overconfidence follows a string of successes;

7) Unwillingness to accept losses, leading to alterations of trade plans after the trade has gone into the red;

6) Loss of confidence in one's trading plan/strategy because it has not been adequately tested and battle-tested;

5) Personality traits that lead to impulsivity and low frustration tolerance in stressful situations;

4) Situational performance pressures, such as trading slumps and increased personal expenses, that change how traders trade (putting P/L ahead of making good trades);

3) Trading positions that are excessive for the account size, created exaggerated P/L swings and emotional reactions;

2) Not having a clearly defined trading plan/strategy in the first place;

1) Trading a time frame, style, or market that does not match your talents, skills, risk tolerance, and personality.

10) Environmental distractions and boredom cause a lack of focus;

9) Fatigue and mental overload create a loss of concentration;

8) Overconfidence follows a string of successes;

7) Unwillingness to accept losses, leading to alterations of trade plans after the trade has gone into the red;

6) Loss of confidence in one's trading plan/strategy because it has not been adequately tested and battle-tested;

5) Personality traits that lead to impulsivity and low frustration tolerance in stressful situations;

4) Situational performance pressures, such as trading slumps and increased personal expenses, that change how traders trade (putting P/L ahead of making good trades);

3) Trading positions that are excessive for the account size, created exaggerated P/L swings and emotional reactions;

2) Not having a clearly defined trading plan/strategy in the first place;

1) Trading a time frame, style, or market that does not match your talents, skills, risk tolerance, and personality.

Monday, June 26, 2006

Why Your Trading Isn't Working Out

A good physician knows that, before cure comes a diagnosis. You cannot treat a problem before you identify what that problem is.

All too often, traders assume that their performance problems are due to a single cause: trading the wrong chart pattern or indicator, having the wrong mindset, etc. As a result, they seek out one trading guru or coach after another, only to see their P/L head steadily south.

The reality is that there are quite a few reasons why trading might be unprofitable. Figuring out which might apply to you is the first step is getting the right help.

Here's a fourfold scheme that I have found helpful in conceptualizing trading problems:

1) Problems of training and experience - Many traders put their money at risk well before they have developed their own trading styles based on the identification of an objective edge in the marketplace. They are not emotionally prepared to handle risk and reward, and they are not sufficiently steeped in markets to separate randomness from meaningful market patterns. They are like beginning golfers who decide to enter a competitive tournament. Their frustrations are the result of lack of preparation and experience. The answer to these problems is to develop a training program that helps you develop confidence and competence in identifying meaningful market patterns and acting upon those. Online trading rooms, where you can observe experienced traders apply their skills, are helpful for this purpose.

2) Problems of changing markets - When traders have had consistent success, but suddenly lose money with consistency, a reasonable hypothesis is that markets have changed and what once was an edge no longer is profitable. This happened to many momentum traders after the late 1990s bull market, and it also has been the case for many scalpers after volatility came out of the stock indices. Here the challenge is to remake one's trading, either by retaining the core strategy and seeking other markets with opportunity or by finding new strategies for one's market. The answer to these problems is to reduce your trading size and re-enter a learning curve to become acquainted with new markets and methods. Figuring out how you learned the markets initially will help you identify steps you need to take to relearn new patterns.

3) Situational emotional problems - These are emotional stresses that are recent in origin and that interfere with decision making and performance. Some of these stresses might pertain to trading, such as frustration after a slump or loss. Some might stem from one's personal life, as in a relationship breakup or increased financial pressures due to a new home or child. Very often these problems create performance anxieties by putting the making of money ahead of the placing of good trades. The answer to these problems is to seek out short-term counseling to help you gain perspective on the problems and cope with them effectively.

4) Ongoing emotional problems - These are emotional patterns that predate trading and that show up in areas of life apart from trading. They include depression, anxiety, anger, attention deficits, and substance abuse. Such problems skew how people experience themselves and the world and lead to biases in processing information. As a result, it is difficult to trade (and manage risk) with consistency. The answer to these problems is to seek out competent professional help from a licensed psychologist or psychiatrist, including (possibly) counseling and medication assistance.

The important point is that not all trading problems are psychological in nature. Sometimes we need to work on the markets, sometimes we need to work on ourselves, and sometimes we need to do both. But first of all, we need to identify what our problems are. If you seek help for your trading concerns, make sure you do so from an individual who is experienced in both trading and psychology. If people only possess hammers, they'll treat you like a nail. You want mentors who possess multiple tools and who can design the kind of help that will be right for you.

For the trader, as the physician, diagnosing problems is the first step toward cure.

All too often, traders assume that their performance problems are due to a single cause: trading the wrong chart pattern or indicator, having the wrong mindset, etc. As a result, they seek out one trading guru or coach after another, only to see their P/L head steadily south.

The reality is that there are quite a few reasons why trading might be unprofitable. Figuring out which might apply to you is the first step is getting the right help.

Here's a fourfold scheme that I have found helpful in conceptualizing trading problems:

1) Problems of training and experience - Many traders put their money at risk well before they have developed their own trading styles based on the identification of an objective edge in the marketplace. They are not emotionally prepared to handle risk and reward, and they are not sufficiently steeped in markets to separate randomness from meaningful market patterns. They are like beginning golfers who decide to enter a competitive tournament. Their frustrations are the result of lack of preparation and experience. The answer to these problems is to develop a training program that helps you develop confidence and competence in identifying meaningful market patterns and acting upon those. Online trading rooms, where you can observe experienced traders apply their skills, are helpful for this purpose.

2) Problems of changing markets - When traders have had consistent success, but suddenly lose money with consistency, a reasonable hypothesis is that markets have changed and what once was an edge no longer is profitable. This happened to many momentum traders after the late 1990s bull market, and it also has been the case for many scalpers after volatility came out of the stock indices. Here the challenge is to remake one's trading, either by retaining the core strategy and seeking other markets with opportunity or by finding new strategies for one's market. The answer to these problems is to reduce your trading size and re-enter a learning curve to become acquainted with new markets and methods. Figuring out how you learned the markets initially will help you identify steps you need to take to relearn new patterns.

3) Situational emotional problems - These are emotional stresses that are recent in origin and that interfere with decision making and performance. Some of these stresses might pertain to trading, such as frustration after a slump or loss. Some might stem from one's personal life, as in a relationship breakup or increased financial pressures due to a new home or child. Very often these problems create performance anxieties by putting the making of money ahead of the placing of good trades. The answer to these problems is to seek out short-term counseling to help you gain perspective on the problems and cope with them effectively.

4) Ongoing emotional problems - These are emotional patterns that predate trading and that show up in areas of life apart from trading. They include depression, anxiety, anger, attention deficits, and substance abuse. Such problems skew how people experience themselves and the world and lead to biases in processing information. As a result, it is difficult to trade (and manage risk) with consistency. The answer to these problems is to seek out competent professional help from a licensed psychologist or psychiatrist, including (possibly) counseling and medication assistance.

The important point is that not all trading problems are psychological in nature. Sometimes we need to work on the markets, sometimes we need to work on ourselves, and sometimes we need to do both. But first of all, we need to identify what our problems are. If you seek help for your trading concerns, make sure you do so from an individual who is experienced in both trading and psychology. If people only possess hammers, they'll treat you like a nail. You want mentors who possess multiple tools and who can design the kind of help that will be right for you.

For the trader, as the physician, diagnosing problems is the first step toward cure.

Double Inside Days

Thanks to a reader who suggested that I look at the phenomenon that we had as of Friday's close, in which Thursday and Friday's action were inside Wednesday's high and low. This double inside day represents a sizable short-term period of consolidation. Interestingly, the pattern has been bullish since 1990 and more specifically from 2004 to the present, where we see favorable returns five days out.

The important pattern, however, is that the double inside day appears to be bullish during bull markets and bearish during bear markets (as in 2000-2002). When you think about it, this makes some sense. By definition, a market's directional activity does not occur during consolidation periods. It's what happens afterward that sets the trend. A market tells you quite a bit by how it behaves in the face of consolidation. This itself might be a useful market indicator.

The important pattern, however, is that the double inside day appears to be bullish during bull markets and bearish during bear markets (as in 2000-2002). When you think about it, this makes some sense. By definition, a market's directional activity does not occur during consolidation periods. It's what happens afterward that sets the trend. A market tells you quite a bit by how it behaves in the face of consolidation. This itself might be a useful market indicator.

Sunday, June 25, 2006

Why It's Valuable to Track the Market Herd

In my upcoming Trading Markets article, I will be examining the ratio of advancing to declining volume as an indication of herd-like behavior in the market. I do this both in the traditional fashion of cumulating volume in advancing stocks vs. volume in declining stocks and in a new, intraday version that cumulates volume in advancing vs. declining ES time periods. The moral of the story is that it's worth tracking the behavior of the trading herd.

Going back to 2004 (N = 621 trading days), we've had 42 days in the S&P 500 Index that have been up by 1% or more. Overall, the market has been up by an average of .06% the next day (24 up, 18 down), not much of an edge over the average gain of .02% (343 up, 278 down) for the entire sample.

When we divide the strong up days in the S&P in half based on the ratio of advancing stock volume to declining stock volume, however, we see an interesting pattern. When the S&P 500 is up strong and volume is heavily concentrated among advancers (i.e., the herd is buying), the next day in the S&P averages a loss of -.07% (10 up, 11 down). When the S&P 500 is up strong and volume is not heavily concentrated among advancers, the next day in the S&P averages a gain of .19% (14 up, 7 down).

It thus appears that strong market rises are more likely to persist in the near term if they are not accepted by the herd.

How about during market declines?

Since 2004, we've had 47 days in which we've had a decline of 1% or greater. Overall, the next day in the S&P 500 Index has been up by an average of .04% (28 up, 19 down). Again, that's not much of an edge compared to the average gain of .02% (343 up, 278 down) for the entire sample.

Here, too, though we see a pattern. When the S&P is down sharply and volume is concentrated in declining issues (N = 23), the next day averages a loss of -.03% (11 up, 12 down). When the S&P is down sharply and volume is not concentrated in declining issues (N = 24), the next day averages a gain of .11% (17 up, 7 down).

What that means is that sharp declines are more likely to persist the next day if the herd is selling. When the decline is large but selling is not indiscriminate across issues, we're more likely to have a snap back the next day.

Finally, let's look at market days that are relatively flat. Since 2004, we've had 84 days in which the S&P 500 Index has closed within a range of plus or minus .10%. The next day, the S&P has averaged a gain of .02% (44 up, 40 down), no edge over the sample as a whole. When volume was relatively concentrated in advancing stocks, however, the next day in the S&P averaged a loss of -.05% (20 up, 22 down). When volume was relatively concentrated in declining stocks, the next day averaged a gain of .10% (24 up, 18 down).

I've looked at this over multiple time frames and the results are similar. When volume is concentrated at one end of the extreme or the other, it generally has meaningful implications for the market's near-term performance.

Going back to 2004 (N = 621 trading days), we've had 42 days in the S&P 500 Index that have been up by 1% or more. Overall, the market has been up by an average of .06% the next day (24 up, 18 down), not much of an edge over the average gain of .02% (343 up, 278 down) for the entire sample.

When we divide the strong up days in the S&P in half based on the ratio of advancing stock volume to declining stock volume, however, we see an interesting pattern. When the S&P 500 is up strong and volume is heavily concentrated among advancers (i.e., the herd is buying), the next day in the S&P averages a loss of -.07% (10 up, 11 down). When the S&P 500 is up strong and volume is not heavily concentrated among advancers, the next day in the S&P averages a gain of .19% (14 up, 7 down).

It thus appears that strong market rises are more likely to persist in the near term if they are not accepted by the herd.

How about during market declines?

Since 2004, we've had 47 days in which we've had a decline of 1% or greater. Overall, the next day in the S&P 500 Index has been up by an average of .04% (28 up, 19 down). Again, that's not much of an edge compared to the average gain of .02% (343 up, 278 down) for the entire sample.

Here, too, though we see a pattern. When the S&P is down sharply and volume is concentrated in declining issues (N = 23), the next day averages a loss of -.03% (11 up, 12 down). When the S&P is down sharply and volume is not concentrated in declining issues (N = 24), the next day averages a gain of .11% (17 up, 7 down).

What that means is that sharp declines are more likely to persist the next day if the herd is selling. When the decline is large but selling is not indiscriminate across issues, we're more likely to have a snap back the next day.

Finally, let's look at market days that are relatively flat. Since 2004, we've had 84 days in which the S&P 500 Index has closed within a range of plus or minus .10%. The next day, the S&P has averaged a gain of .02% (44 up, 40 down), no edge over the sample as a whole. When volume was relatively concentrated in advancing stocks, however, the next day in the S&P averaged a loss of -.05% (20 up, 22 down). When volume was relatively concentrated in declining stocks, the next day averaged a gain of .10% (24 up, 18 down).

I've looked at this over multiple time frames and the results are similar. When volume is concentrated at one end of the extreme or the other, it generally has meaningful implications for the market's near-term performance.

Saturday, June 24, 2006

How to Kill a Trending Market

One of the best ways of killing a trending market is to develop a tradable index for it. And if you really want to drive a stake in its heart, you develop multiple tradable indices.

Why?

The indices provide arbitrage opportunities, which mean that an increasing proportion of volume is devoted to keeping stocks in line with the index, index 1 in line with index 2, etc.

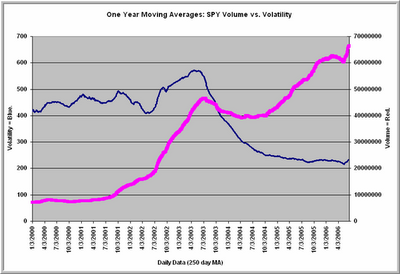

That's how you get the chart above, which tracks average volume and volatility in SPY from 2000 to the present. Note that volume in SPY has steadily risen to all time highs. Volatility, however, has steadily decreased from 2003 to the present, the recent uptick notwithstanding.

With the recent hyperexpansion of ETFs, this has important implications. Increased liquidity over time will bring a range of markets to the average stock trader that, to this point, have not been available. With that volume, however, may come trading patterns that make the market harder to trade with traditional momentum/trend tools.

In a recent study, I showed how the propensity to trend has been coming out of the S&P market on a long-term basis. If I'm right, this might be the future for those stock sectors and markets that attract significant attention from index players. Automated index arbitrage brings significant volume to markets, but it is not necessarily the volume that contributes to directional market trade.

Friday, June 23, 2006

Trending Behavior and Short-Term Stock Index Performance

I'm in the process of studying short-term market trending and its impact on prices in the near term. My Power Measure, charted each day on the Trading Psychology Weblog, is a metric that captures the propensity of any market to behave in a trending way. It is scaled in such as way as to vary between +100 (perfect upside trending) and -100 (perfect downside trending), with zero representing the complete absence of trending.

Readings of +90 or greater, interestingly, are associated with stronger prices in the near term. Since March of this year (N = 1894 15-minute periods), we've had 98 occasions in which the Power Measure has exceeded +90. The market (SPY) six hours later has averaged a gain of .10% (57 up, 41 down). When the Power Measure has been positive (greater than +20) but less than +90, the next six hours in SPY have averaged a loss of -.12% (291 up, 385 down).

What this suggests is that vigorous bull trends tend to continue in the near term, but moderately positive ones are subject to reversal.

What I'm also seeing is a relationship between intraday volume and trendiness. When the trend is very strong and positive (greater than +90), but volume is relatively light (N = 49), the next six hours in SPY average a solid gain of .17%. When trendiness is strong to the upside and volume is relatively high (N = 50), the next six hours in SPY only averages a gain of .02%.

Similarly, when trendiness is strong and negative (less than -90), but volume is relatively light (N = 59), the next six hours in SPY average a gain of .06%. When trendiness is strong to the downside and volume is relatively heavy (N = 58), the next six hours in SPY average a loss of -.11%. High volume during a strong bullish trend appears to lead to short-term underperformance; high volume during a strong bearish trend appears to lead to further short-term bearish performance.

These are very preliminary findings, with much more study to come. The goal is to see when trends tend to continue and when they tend to reverse.

Readings of +90 or greater, interestingly, are associated with stronger prices in the near term. Since March of this year (N = 1894 15-minute periods), we've had 98 occasions in which the Power Measure has exceeded +90. The market (SPY) six hours later has averaged a gain of .10% (57 up, 41 down). When the Power Measure has been positive (greater than +20) but less than +90, the next six hours in SPY have averaged a loss of -.12% (291 up, 385 down).

What this suggests is that vigorous bull trends tend to continue in the near term, but moderately positive ones are subject to reversal.

What I'm also seeing is a relationship between intraday volume and trendiness. When the trend is very strong and positive (greater than +90), but volume is relatively light (N = 49), the next six hours in SPY average a solid gain of .17%. When trendiness is strong to the upside and volume is relatively high (N = 50), the next six hours in SPY only averages a gain of .02%.

Similarly, when trendiness is strong and negative (less than -90), but volume is relatively light (N = 59), the next six hours in SPY average a gain of .06%. When trendiness is strong to the downside and volume is relatively heavy (N = 58), the next six hours in SPY average a loss of -.11%. High volume during a strong bullish trend appears to lead to short-term underperformance; high volume during a strong bearish trend appears to lead to further short-term bearish performance.

These are very preliminary findings, with much more study to come. The goal is to see when trends tend to continue and when they tend to reverse.

Thursday, June 22, 2006

Opportunity During the Day Trading Session

In the last post, we saw that the strategy of closing positions out at the end of the day takes traders out of the most bullish portion of market action.

But how much price action can be expected during the day session, from open to close? Since March, 2003 (N = 834 trading days), we had 477 days in SPY--almost 60%--in which the market closed within a .50% band around its open. Only 135 day sessions (a little over 15%) saw a gain of over 1% from open to close or a loss of greater than 1%. Surprisingly, about 40% of all day sessions closed within a band of .30% around the open.

The average high-low range since March, 2003 has been 1.07%--and yet only a little more than 15% of all days closed with a day session price change of more than 1%. What that tells us is how few of those days were directional, trend days. While the average trading day may give us approximately 1% of range, the average open-to-close change is far smaller than that. Indeed, about 40% of the time, the day's price change has been less than four points in either direction.

But how much price action can be expected during the day session, from open to close? Since March, 2003 (N = 834 trading days), we had 477 days in SPY--almost 60%--in which the market closed within a .50% band around its open. Only 135 day sessions (a little over 15%) saw a gain of over 1% from open to close or a loss of greater than 1%. Surprisingly, about 40% of all day sessions closed within a band of .30% around the open.

The average high-low range since March, 2003 has been 1.07%--and yet only a little more than 15% of all days closed with a day session price change of more than 1%. What that tells us is how few of those days were directional, trend days. While the average trading day may give us approximately 1% of range, the average open-to-close change is far smaller than that. Indeed, about 40% of the time, the day's price change has been less than four points in either direction.

Wednesday, June 21, 2006

Playing It Safe is the Riskiest Strategy

In my post on "what you know can hurt you", I made the point that markets reward the assumption of risk, not the pursuit of the familiar.

Here's another case in point.

Since January, 1997, we've gained 50+ points in SPY, or the equivalent of over 500 S&P points.

So you'd think it was a reasonably good market for daytraders over that time.

Wrong.

Daytraders like to close positions out by the end of the day to avoid overnight risk. But markets don't reward the avoidance of risk.

From the close to the next day's open, from January, 1997 to the present (N = 2402 trading days), SPY gained a total of over 139 points. During that same period, from the day's open to the day's close (the daytrading market), SPY *lost* a total of 88 points.

So, in other words, daytraders who bought the open and sold the close every day during a period of rising market prices lost about 880 S&P points.

But maybe you're thinking this underperformance was just a function of the 2000-2003 bear market.

From 2003 to the present (the most recent bull market), SPY from the close to the next day's open gained a total of almost 36 points. And the daytrading market (open to close)? During the entire recent bull market SPY gained a total of four points. In 2006 thus far, SPY has gained about 6.6 points from the close to the next day's open. During the daytrading market, we've lost about 6.1 points.

It's awfully hard to find *any* recent time period in which the "safe" strategy of closing positions at the end of the day provided traders with opportunity.

Markets are a lot like relationships: Playing it really safe is often the riskiest strategy.

Here's another case in point.

Since January, 1997, we've gained 50+ points in SPY, or the equivalent of over 500 S&P points.

So you'd think it was a reasonably good market for daytraders over that time.

Wrong.

Daytraders like to close positions out by the end of the day to avoid overnight risk. But markets don't reward the avoidance of risk.

From the close to the next day's open, from January, 1997 to the present (N = 2402 trading days), SPY gained a total of over 139 points. During that same period, from the day's open to the day's close (the daytrading market), SPY *lost* a total of 88 points.

So, in other words, daytraders who bought the open and sold the close every day during a period of rising market prices lost about 880 S&P points.

But maybe you're thinking this underperformance was just a function of the 2000-2003 bear market.

From 2003 to the present (the most recent bull market), SPY from the close to the next day's open gained a total of almost 36 points. And the daytrading market (open to close)? During the entire recent bull market SPY gained a total of four points. In 2006 thus far, SPY has gained about 6.6 points from the close to the next day's open. During the daytrading market, we've lost about 6.1 points.

It's awfully hard to find *any* recent time period in which the "safe" strategy of closing positions at the end of the day provided traders with opportunity.

Markets are a lot like relationships: Playing it really safe is often the riskiest strategy.

Inside Day With Less Fear: What It Means

On Tuesday we saw yet another inside day, with a sizable reduction in the closing VIX. Overall, the short-term outlook following inside days is not bullish. Since March, 2003 (N = 830 trading days), we've had 112 inside days in the S&P 500 (SPY). Two days later, the market averaged a flat performance (52 up, 60 down), considerably worse than the average two-day gain of .12% (394 up, 324 down) for the remainder of the sample.

When the inside day has been accompanied by a large drop in the VIX (N = 56), the next two days in SPY have averaged a loss of -.03% (22 up, 34 down). Relative strength in the VIX (N = 56) during an inside day has been associated with an average two-day gain of .03% (30 up, 26 down).

In short, inside days seem to provide little edge for the bulls, especially when they are accompanied by a reduction in fear among options participants.

When the inside day has been accompanied by a large drop in the VIX (N = 56), the next two days in SPY have averaged a loss of -.03% (22 up, 34 down). Relative strength in the VIX (N = 56) during an inside day has been associated with an average two-day gain of .03% (30 up, 26 down).

In short, inside days seem to provide little edge for the bulls, especially when they are accompanied by a reduction in fear among options participants.

Tuesday, June 20, 2006

Intraday Volatility: What We Can Learn From Volume Patterns

We are seeing enhanced volatility at every time frame during this recent market decline. In today's entry for the Trading Psychology Weblog, I posted a chart that showed how dramatically the VIX itself has become more volatile on a day-to-day basis.

Intraday, from March through the end of April, the average 15-minute range in the ES futures was 2.2 points. From May through June 15th, the average 15-minute range was 2.9 points. The average three-hour range from March through April was .59%. Since May, it has been .81%.

Why is volatility greater? Perhaps it is a function of *who* is in the marketplace. From March through April, the average 15-minute ES volume was 30,330. Since May, it has been 40,911. We've been hearing how "fast money" hedge funds and other money managers have been liquidating volatile positions during this time. Maybe, just maybe, we're seeing 33% more volume and similar higher volatility because of *their* enhanced participation.

I look at it this way. The locals participate every day in the market. The average daily volume probably represents their normal participation in the marketplace. When volume--and hence volatility--spike above normal, that's probably because other time-frame participants have come to the market: mutual funds, hedge funds, investment banks, etc. They only come to market when they perceive relative value or overvalue in an asset class.

By looking at volume that way, you can figure out the price points at which these savvy players discern value--and overvalue. You can also figure out where those value points are shifting and where they remain in force as mean values for eventual reversion. Remember: locals provide liquidity and govern the next few ticks; institutions provide market direction over the next few days. How many traders get stopped out of good positions because they lose a few ticks to the locals and lose sight of the market's bigger picture determined by other-timeframe participants?

Intraday, from March through the end of April, the average 15-minute range in the ES futures was 2.2 points. From May through June 15th, the average 15-minute range was 2.9 points. The average three-hour range from March through April was .59%. Since May, it has been .81%.

Why is volatility greater? Perhaps it is a function of *who* is in the marketplace. From March through April, the average 15-minute ES volume was 30,330. Since May, it has been 40,911. We've been hearing how "fast money" hedge funds and other money managers have been liquidating volatile positions during this time. Maybe, just maybe, we're seeing 33% more volume and similar higher volatility because of *their* enhanced participation.

I look at it this way. The locals participate every day in the market. The average daily volume probably represents their normal participation in the marketplace. When volume--and hence volatility--spike above normal, that's probably because other time-frame participants have come to the market: mutual funds, hedge funds, investment banks, etc. They only come to market when they perceive relative value or overvalue in an asset class.

By looking at volume that way, you can figure out the price points at which these savvy players discern value--and overvalue. You can also figure out where those value points are shifting and where they remain in force as mean values for eventual reversion. Remember: locals provide liquidity and govern the next few ticks; institutions provide market direction over the next few days. How many traders get stopped out of good positions because they lose a few ticks to the locals and lose sight of the market's bigger picture determined by other-timeframe participants?

Monday, June 19, 2006

Inside Day After a Big Rise: What Happens Next

Thursday was a strong day in the stock indices, and Friday retraced some of those gains as an inside day.

I went back to December, 1996 (N = 2395 trading days) and found 18 occurrences of down inside days following strong gains of 1.5% or more in SPY. Interestingly, expectations were not favorable over the next two days. SPY averaged a loss of -.24% (8 up, 10 down) two days after the inside day--much weaker than the average two-day gain of .06% for the entire sample.

The same pattern held true for inside days following gains of 1% or more (N = 39).

Perhaps the most interesting finding is that we haven't seen such a pattern (up more than 1.5% followed by a down, inside day) since December, 2002. We've seen four rises of 1% or more followed by down, inside days since the recent bull market began in 2003; three of those four occasions were down one day later.

We're up nicely prior to the open as I'm writing this thanks to overseas strength. We'll see if this proves an exception to the pattern.

I went back to December, 1996 (N = 2395 trading days) and found 18 occurrences of down inside days following strong gains of 1.5% or more in SPY. Interestingly, expectations were not favorable over the next two days. SPY averaged a loss of -.24% (8 up, 10 down) two days after the inside day--much weaker than the average two-day gain of .06% for the entire sample.

The same pattern held true for inside days following gains of 1% or more (N = 39).

Perhaps the most interesting finding is that we haven't seen such a pattern (up more than 1.5% followed by a down, inside day) since December, 2002. We've seen four rises of 1% or more followed by down, inside days since the recent bull market began in 2003; three of those four occasions were down one day later.

We're up nicely prior to the open as I'm writing this thanks to overseas strength. We'll see if this proves an exception to the pattern.

Sunday, June 18, 2006

What You Know Can Hurt You

What you trade is every bit as important as how you trade. In spite of this, we see from volume figures that the majority of traders stick with the tried and true familiar stock indices. While these provide liquidity, do they provide performance?

In fact not. The more familiar the stocks, the worse their performance during the recent bull market.

For example: Since May, 2003, here have been the returns from various indices:

S&P growth stocks (IVW): 22%

S&P value stocks (IVE): 53%

S&P 500 Equal-Weight Index (RSP): 65%

Russell 2000 Index (IWM): 74%

German Index (EWG): 99%

Japan Index (EWJ): 101%

Emerging Markets Index (EEM): 153%

Chances are good, if it was a stock or market familiar to you, it has underperformed. Large cap growth has underperformed. The U.S. has underperformed.

Ask yourself where hedge funds have put their money to work; then ask yourself where Joe Investor has parked his mutual fund money.

Markets reward the assumption of risk, not the pursuit of the familiar.

In fact not. The more familiar the stocks, the worse their performance during the recent bull market.

For example: Since May, 2003, here have been the returns from various indices:

S&P growth stocks (IVW): 22%

S&P value stocks (IVE): 53%

S&P 500 Equal-Weight Index (RSP): 65%

Russell 2000 Index (IWM): 74%

German Index (EWG): 99%

Japan Index (EWJ): 101%

Emerging Markets Index (EEM): 153%

Chances are good, if it was a stock or market familiar to you, it has underperformed. Large cap growth has underperformed. The U.S. has underperformed.

Ask yourself where hedge funds have put their money to work; then ask yourself where Joe Investor has parked his mutual fund money.

Markets reward the assumption of risk, not the pursuit of the familiar.

Friday, June 16, 2006

Why This is Not *the* Bottom

Has the bear bottomed? That was the question I heard with surprising frequency after Thursday's rally. My answer has been, "No. It takes a lot more weakness to make for a cyclical bear market bottom."

Let's look at the historical record:

1966 cyclical bottom: 56% of all stocks make 52-week lows on August 29th.

1970 cyclical bottom: 58% of all stocks make 52-week lows on May 26th.

1974 cyclical bottom: 37% of all stocks make 52-week lows on September 13th.

1978 cyclical bottom: 30% of all stocks make 52-week lows on October 30th.

1980 cyclical bottom: 38% of all stocks make 52-week lows on March 27th.

1981 cyclical bottom: 31% of all stocks make 52-week lows on September 28th.

1987 cyclical bottom: 57% of all stocks make 52-week lows on October 20th.

1990 cyclical bottom: 35% of all stocks make 52-week lows on August 23rd.

1994 cyclical bottom: 23% of all stocks make 52-week lows on April 4th.

1998 cyclical bottom: 33% of all stocks make 52-week lows on August 31st.

2002 cyclical bottom: 27% of all stocks make 52-week lows on July 24th.

2006 cyclical bottom??: 8% of all stocks make 52-week lows on June 13th.

I don't think so.

Notice the average spacing of the cyclical bottoms. Those bottoms don't occur until bearishness is rampant, and that typically takes a large proportion of issues making fresh lows.

Notice something else very important: The point at which we hit maximum new lows is rarely the eventual price low for the cyclical decline. For instance, we had 27% of stocks making new lows in July, 2002, but we saw further price lows in October of that year and March of 2003. Similarly, we saw 31% of stocks making new lows in September, 1981, but didn't see actual price lows until August of 1982.

So what we're seeing in the current market is either a normal correction in a bull market (like we had in October, 2005 and May, 2004), or it is just the *start* of a full-fledged cyclical bear market that has much further to go. The quality of the next intermediate-term rally should go a long way toward identifying which scenario we're in.

Let's look at the historical record:

1966 cyclical bottom: 56% of all stocks make 52-week lows on August 29th.

1970 cyclical bottom: 58% of all stocks make 52-week lows on May 26th.

1974 cyclical bottom: 37% of all stocks make 52-week lows on September 13th.

1978 cyclical bottom: 30% of all stocks make 52-week lows on October 30th.

1980 cyclical bottom: 38% of all stocks make 52-week lows on March 27th.

1981 cyclical bottom: 31% of all stocks make 52-week lows on September 28th.

1987 cyclical bottom: 57% of all stocks make 52-week lows on October 20th.

1990 cyclical bottom: 35% of all stocks make 52-week lows on August 23rd.

1994 cyclical bottom: 23% of all stocks make 52-week lows on April 4th.

1998 cyclical bottom: 33% of all stocks make 52-week lows on August 31st.

2002 cyclical bottom: 27% of all stocks make 52-week lows on July 24th.

2006 cyclical bottom??: 8% of all stocks make 52-week lows on June 13th.

I don't think so.

Notice the average spacing of the cyclical bottoms. Those bottoms don't occur until bearishness is rampant, and that typically takes a large proportion of issues making fresh lows.

Notice something else very important: The point at which we hit maximum new lows is rarely the eventual price low for the cyclical decline. For instance, we had 27% of stocks making new lows in July, 2002, but we saw further price lows in October of that year and March of 2003. Similarly, we saw 31% of stocks making new lows in September, 1981, but didn't see actual price lows until August of 1982.

So what we're seeing in the current market is either a normal correction in a bull market (like we had in October, 2005 and May, 2004), or it is just the *start* of a full-fledged cyclical bear market that has much further to go. The quality of the next intermediate-term rally should go a long way toward identifying which scenario we're in.

Big Up Day In Oversold Market: What Next?

NOTE: There will be an update of the Trading Psychology Weblog tonight.

Thursday was a very broad rally in a market that had been sharply lower for the month. Specifically, the S&P 500 Index gained over 2% on the day after having been down about 4.8% during the previous 20 sessions.

I went back to 1996 (N = 2629 trading days) to see what happens after we get a 2%+ rally after a 20-day period in which the market has been down over 4%. This occurred 40 times. Five days later, the S&P 500 Index was up by an average of .55% (24 up, 16 down), stronger than the average five-day gain of .16% (1434 up, 1195 down) for the entire sample. Twenty-three of the occasions took place during the 2000-2002 bear market, and, overall, the strong up days after 20 days of weakness tended to be followed by considerable volatility.

The ratio of up volume to down volume on Thursday was huge: over 22:1. That is the strongest concentration of volume we've seen since 1996. Interestingly, when the market rallied strongly after 20 days of weakness *and* volume was highly concentrated in the advancing stocks (N = 14), the next day in the S&P averaged a loss of -.41% (6 up, 8 down), considerably weaker than normal. Similarly, when we've had a strong rally in a down market and the day's Arms Index (TRIN) has been less than .40 (N = 16), the next two days in the S&P have averaged a loss of -.32% (6 up, 10 down).

In summary, strong up days in a down market, in which volume is highly concentrated in the advancing issues, actually yield subnormal returns in the short run. Moreover, many of these big up days during falling markets occurred during bear markets and did not signal an end to the bear. While strong up days *in general* tend to produce favorable near-term results, panic buying/short-covering after a period of bearishness has not produced favorable returns over the next couple of days.

Thursday was a very broad rally in a market that had been sharply lower for the month. Specifically, the S&P 500 Index gained over 2% on the day after having been down about 4.8% during the previous 20 sessions.

I went back to 1996 (N = 2629 trading days) to see what happens after we get a 2%+ rally after a 20-day period in which the market has been down over 4%. This occurred 40 times. Five days later, the S&P 500 Index was up by an average of .55% (24 up, 16 down), stronger than the average five-day gain of .16% (1434 up, 1195 down) for the entire sample. Twenty-three of the occasions took place during the 2000-2002 bear market, and, overall, the strong up days after 20 days of weakness tended to be followed by considerable volatility.

The ratio of up volume to down volume on Thursday was huge: over 22:1. That is the strongest concentration of volume we've seen since 1996. Interestingly, when the market rallied strongly after 20 days of weakness *and* volume was highly concentrated in the advancing stocks (N = 14), the next day in the S&P averaged a loss of -.41% (6 up, 8 down), considerably weaker than normal. Similarly, when we've had a strong rally in a down market and the day's Arms Index (TRIN) has been less than .40 (N = 16), the next two days in the S&P have averaged a loss of -.32% (6 up, 10 down).

In summary, strong up days in a down market, in which volume is highly concentrated in the advancing issues, actually yield subnormal returns in the short run. Moreover, many of these big up days during falling markets occurred during bear markets and did not signal an end to the bear. While strong up days *in general* tend to produce favorable near-term results, panic buying/short-covering after a period of bearishness has not produced favorable returns over the next couple of days.

Thursday, June 15, 2006

Blueprint for an Uncompromised Life - Part Five: Multiplier Effects

Note: This is the final installment in the five-part series that examines the factors that contribute to extraordinary creative achievement. My regular postings to TraderFeed and the Trading Psychology Weblog will commence on Friday.

We have seen that expert performers in their fields undergo a very specific developmental process, beginning with crystallizing experiences, mentorship, and the achievement of competence through structured practice. Equally important, expert performers follow a different developmental trajectory from their less accomplished peers.

This developmental trajectory takes advantage of what researchers call multiplier effects. A simple example from Sandra Scarr's research on intellectual development will illustrate the power of these effects. Young children with high and low IQs follow very different life paths on average, though they start from similar upbringings. This is because the high IQ children tend to seek out higher IQ peers and thus receive more intellectual stimulation from their environment. They also are more likely to be targeted for enriched academic experiences. Over time, these differences compound, creating multiplier effects and widely diverging developmental paths.

Consider two intern traders at a trading firm: one shows initial talent for reading short-term market patterns, the other picks up the patterns more slowly. Initially, their P/L differs only modestly. The quicker student, however, is selected by the firm's top trader as a member of that trading team and is given extensive mentoring. The slower student is not provided this enriched experience. As a result, by the end of the year, the two students are following very different career paths, with a wide performance gap.

We see a similar phenomenon when children born earlier in the year have physically matured to a greater degree than children born later in the year and hence tend to be selected for enriched Little League and other athletic experiences. The initial gap in performance widens as the mature children are provided superior experiences relative to their peers.

Multiplier effects mean that what is inborn to the individual--talents--help to shape environmental experiences that in turn maximize these talents. Highly successful individuals place themselves in environments that take maximum advantage of their interests, talents, and skills.

Nothing is more important for traders--and people in general--than to find their niches: those settings that will help them make the most of who they are. Many traders think they are not reaching their potential because of emotional blocks. Often, however, their performance blocks are of a very different nature: they are not trading the markets or styles that capitalize on their talents and supercharge their learning and P/L through multiplier effects.

We have seen that expert performers in their fields undergo a very specific developmental process, beginning with crystallizing experiences, mentorship, and the achievement of competence through structured practice. Equally important, expert performers follow a different developmental trajectory from their less accomplished peers.

This developmental trajectory takes advantage of what researchers call multiplier effects. A simple example from Sandra Scarr's research on intellectual development will illustrate the power of these effects. Young children with high and low IQs follow very different life paths on average, though they start from similar upbringings. This is because the high IQ children tend to seek out higher IQ peers and thus receive more intellectual stimulation from their environment. They also are more likely to be targeted for enriched academic experiences. Over time, these differences compound, creating multiplier effects and widely diverging developmental paths.

Consider two intern traders at a trading firm: one shows initial talent for reading short-term market patterns, the other picks up the patterns more slowly. Initially, their P/L differs only modestly. The quicker student, however, is selected by the firm's top trader as a member of that trading team and is given extensive mentoring. The slower student is not provided this enriched experience. As a result, by the end of the year, the two students are following very different career paths, with a wide performance gap.

We see a similar phenomenon when children born earlier in the year have physically matured to a greater degree than children born later in the year and hence tend to be selected for enriched Little League and other athletic experiences. The initial gap in performance widens as the mature children are provided superior experiences relative to their peers.

Multiplier effects mean that what is inborn to the individual--talents--help to shape environmental experiences that in turn maximize these talents. Highly successful individuals place themselves in environments that take maximum advantage of their interests, talents, and skills.

Nothing is more important for traders--and people in general--than to find their niches: those settings that will help them make the most of who they are. Many traders think they are not reaching their potential because of emotional blocks. Often, however, their performance blocks are of a very different nature: they are not trading the markets or styles that capitalize on their talents and supercharge their learning and P/L through multiplier effects.

Market Update

A late bounce pushed the major averages higher, but we continue to see broad weakness. For example, across the entire market of operating company stocks, we see 150 stocks making fresh 20-day highs and 2301 making new lows.

It is instructive to see which sectors have been strongest and weakest this past month. The weakest sectors have included gold stocks, mining issues, industrial equipment, farm machinery, basic materials, cement, and oil/gas drilling and services. Those include prior bull market leaders.

Interestingly, the strongest sectors over the past month have included banks, REITS, and utilities. Not exactly the sectors you'd expect to be strong if the market thought interest rates would continue to rise.

It is instructive to see which sectors have been strongest and weakest this past month. The weakest sectors have included gold stocks, mining issues, industrial equipment, farm machinery, basic materials, cement, and oil/gas drilling and services. Those include prior bull market leaders.

Interestingly, the strongest sectors over the past month have included banks, REITS, and utilities. Not exactly the sectors you'd expect to be strong if the market thought interest rates would continue to rise.

Wednesday, June 14, 2006

Blueprint for an Uncompromised Life - Part Four: Enhancement of Perception

NOTE: I will return from vacation on Friday and will begin regular posts here and to the Trading Psychology Weblog that same day.

As I researched a variety of fields for my new book and examined the ingredients of expert performance, one set of findings jumped out at me. Because highly accomplished performers undergo a lengthy training (formal or informal) through their immersive developmental process, they acquire unique perceptual skills. Years of painting, experimenting with different materials, and closely observing their subject matter enables artists to *see* the world in fresh ways. Similarly, the iterative trial and error process of experimentation allows scientists to perceive unique relationships in nature. Much of this enhancement of perception is a function of cognitive organization: expert performers learn to identify meaningful relationships and use these to organize and interpret what they see. This is how an expert physician, for example, can rapidly diagnose and triage patients in a busy emergency room. It is also how a hockey player learns to skate where the puck will be, not just where it currently is.

It is difficult to appreciate that expert performers do not see the world as do others. Chess grandmasters see a different chessboard than novices; a baseball hitter sees the release of a 95 mph fastball differently than a fan. Experts see the world in terms of meaningful relationships--and because they have acquired a huge library of such relationships after years of observation and practice--they develop elaborate mental maps for guiding their actions.

This has immense relevance for trading, where expert traders see markets differently from beginners. An expert trader might look at a depth of market (DOM) display and notice that, at a prior support level, large traders are pulling bids when they're being hit, but that they are not doing the same with their offers. That allows the expert to sell the market while the rookie is staring at a chart, counting on support.

Similarly, an expert trader observes what is happening in gold, other metals, emerging equity markets, currencies, and interest rates and sees a transition from an expansionary, inflationary market to one that is counting on contraction and a tightening of monetary conditions. The rookie simply sees falling markets and oversold levels on a short-term oscillator.

The expert, in general, develops a richer, more complex, more meaning-laden map of the world than the novice.

Because of that, the expert also lives in a subjective world that is more filled with meaning. A gourmet meal means much more to a connoisseur than to the average person; an accomplished artist sees more in a sunset than the average Joe.

In enhancing ourselves, we enhance our enjoyment of life and make the most of our experience while we're here. The development of expertise is not simply about becoming a great trader, athlete, leader, or artist. It is about cultivating the richest experience of life possible to each of us.

As I researched a variety of fields for my new book and examined the ingredients of expert performance, one set of findings jumped out at me. Because highly accomplished performers undergo a lengthy training (formal or informal) through their immersive developmental process, they acquire unique perceptual skills. Years of painting, experimenting with different materials, and closely observing their subject matter enables artists to *see* the world in fresh ways. Similarly, the iterative trial and error process of experimentation allows scientists to perceive unique relationships in nature. Much of this enhancement of perception is a function of cognitive organization: expert performers learn to identify meaningful relationships and use these to organize and interpret what they see. This is how an expert physician, for example, can rapidly diagnose and triage patients in a busy emergency room. It is also how a hockey player learns to skate where the puck will be, not just where it currently is.

It is difficult to appreciate that expert performers do not see the world as do others. Chess grandmasters see a different chessboard than novices; a baseball hitter sees the release of a 95 mph fastball differently than a fan. Experts see the world in terms of meaningful relationships--and because they have acquired a huge library of such relationships after years of observation and practice--they develop elaborate mental maps for guiding their actions.

This has immense relevance for trading, where expert traders see markets differently from beginners. An expert trader might look at a depth of market (DOM) display and notice that, at a prior support level, large traders are pulling bids when they're being hit, but that they are not doing the same with their offers. That allows the expert to sell the market while the rookie is staring at a chart, counting on support.

Similarly, an expert trader observes what is happening in gold, other metals, emerging equity markets, currencies, and interest rates and sees a transition from an expansionary, inflationary market to one that is counting on contraction and a tightening of monetary conditions. The rookie simply sees falling markets and oversold levels on a short-term oscillator.

The expert, in general, develops a richer, more complex, more meaning-laden map of the world than the novice.

Because of that, the expert also lives in a subjective world that is more filled with meaning. A gourmet meal means much more to a connoisseur than to the average person; an accomplished artist sees more in a sunset than the average Joe.

In enhancing ourselves, we enhance our enjoyment of life and make the most of our experience while we're here. The development of expertise is not simply about becoming a great trader, athlete, leader, or artist. It is about cultivating the richest experience of life possible to each of us.

Market Update

Per the previous update, it's clear why it's important to monitor the strength/weakness of the market during declines such as the one we've been having. If you research price declines alone, you'll come to the conclusion that the market's outlook is bullish following a sharp decline. If, however, you examine the momentum of the decline and the degree to which the broad list of stocks is participating in the decline, another set of conclusions comes to the fore. Short-term market outcomes are not bullish during declines in which an expanding proportion of stocks participates to the downside.

And that is what we've been seeing. On Tuesday, we saw an expanding number of stocks making fresh lows: 222 new 20-day highs against 3146 new lows. Although we did not see an expanding set of new 52-week lows in the SPX stocks, such an expansion was clear in the broad market--and especially among small caps.

We *are* nearing a juncture from which rallies have tended to occur. After Tuesday, only about 18% of SPX stocks are trading above their 52-week moving averages.

Still, this market is all about unwinding the speculative trade that came from easy money. As long as we see the weakness in gold and in emerging markets, this theme holds sway and will influence the broad list of stocks. In spite of violent short-covering rallies, it will take price declines with *fewer* stocks participating to the downside to get me to entertain the bullish side.

And that is what we've been seeing. On Tuesday, we saw an expanding number of stocks making fresh lows: 222 new 20-day highs against 3146 new lows. Although we did not see an expanding set of new 52-week lows in the SPX stocks, such an expansion was clear in the broad market--and especially among small caps.

We *are* nearing a juncture from which rallies have tended to occur. After Tuesday, only about 18% of SPX stocks are trading above their 52-week moving averages.

Still, this market is all about unwinding the speculative trade that came from easy money. As long as we see the weakness in gold and in emerging markets, this theme holds sway and will influence the broad list of stocks. In spite of violent short-covering rallies, it will take price declines with *fewer* stocks participating to the downside to get me to entertain the bullish side.

Tuesday, June 13, 2006

Blueprint for an Uncompromised Life - Part Three: Resilience

One of the most notable findings in the research on extraordinary creative achievement is that even the greatest performers in their fields produce the same ratio of undistinguished works to notable ones through their careers. Great scientists conduct many unsuccessful experiments; outstanding artists produce many paintings and works of music that never win recognition. Many of the greatest home run hitters have are also leaders in strike outs; the most successful companies, like the best actors and directors, also produce many flops in the marketplace.

What makes the expert performer distinctive, researcher Dean Keith Simonton has found, is that he or she is so productive that it becomes more likely that enough successful experiences will accumulate to leave behind a legacy of achievement. We can think of this in evolutionary terms: the great individual produces many more mutations than the average person. Most of these mutations die off, but those who have produced the most variations will, in the end, have the best chance of being represented among the survivors.

This has huge relevance to trading, as it is not necessarily the case that the most successful traders are the ones with the highest ratio of wins to losses. Very successful traders have typically undergone very significant losses. Because, however, they stay in the game longer--through sufficient capital and superior risk management--they are more likely to eventually enjoy and compound the large winning trades than the average trader.

What this means is that a prerequisite of a high level of success is a high level of resilience with respect to loss and defeat. If the greatest individuals are the ones who are most productive, they will also be the ones with the most failed efforts. Research on psychological resilience suggests that people can survive and even thrive in conditions that others find traumatic. Their coping methods enable them to find meaning and purpose even in the greatest adversity, and they are most likely to maintain social and emotional ties during the hardest times.

In my own studies of traders, I have found a correlation between the success of the trader and the degree to which the trader utilizes problem-focused coping and a coping mechanism called "positive reappraisal". The successful individuals deal with problems as they occur, rather than become wrapped up in blaming of self or others. After they have dealt with the problems, they look back on their experience and try to take away something positive from the experience. For them, adversity becomes a tool of learning--not a defeat.

There are traders who are defeated by losses and there are traders who cope with losses. The highly successful individual, however, is the one who turns losses into gains by generating learning experiences and continuous self-improvement.

What makes the expert performer distinctive, researcher Dean Keith Simonton has found, is that he or she is so productive that it becomes more likely that enough successful experiences will accumulate to leave behind a legacy of achievement. We can think of this in evolutionary terms: the great individual produces many more mutations than the average person. Most of these mutations die off, but those who have produced the most variations will, in the end, have the best chance of being represented among the survivors.

This has huge relevance to trading, as it is not necessarily the case that the most successful traders are the ones with the highest ratio of wins to losses. Very successful traders have typically undergone very significant losses. Because, however, they stay in the game longer--through sufficient capital and superior risk management--they are more likely to eventually enjoy and compound the large winning trades than the average trader.

What this means is that a prerequisite of a high level of success is a high level of resilience with respect to loss and defeat. If the greatest individuals are the ones who are most productive, they will also be the ones with the most failed efforts. Research on psychological resilience suggests that people can survive and even thrive in conditions that others find traumatic. Their coping methods enable them to find meaning and purpose even in the greatest adversity, and they are most likely to maintain social and emotional ties during the hardest times.

In my own studies of traders, I have found a correlation between the success of the trader and the degree to which the trader utilizes problem-focused coping and a coping mechanism called "positive reappraisal". The successful individuals deal with problems as they occur, rather than become wrapped up in blaming of self or others. After they have dealt with the problems, they look back on their experience and try to take away something positive from the experience. For them, adversity becomes a tool of learning--not a defeat.

There are traders who are defeated by losses and there are traders who cope with losses. The highly successful individual, however, is the one who turns losses into gains by generating learning experiences and continuous self-improvement.

Monday, June 12, 2006

Market Update

Just a few notes from Monday's trading that might be of relevance. We continue to see broad market weakness. For instance, there were 5 issues in the S&P 600 small caps making new 52-week highs on Monday and 33 making new lows. That is the highest number of new lows since the recent weakness began. In the broad market, 315 issues made 20-day new highs; 1732 made new lows, indicating that last week's late bounce has not kept many issues off their lows. I notice that about 23% of S&P 500 stocks are above their 50-day moving averages. Typically, in the past several years, we've had to get below 20% to reach an intermediate-term market bottom. In all, plenty of reason to stay defensive.

Blueprint for an Uncompromised Life - Part Two: Devotion to Development

Perhaps the key take-away idea from my forthcoming book is that greatness is the outcome of a prolonged developmental process. It is not merely something people are born with, nor is it solely the result of hard work. Greatness lies at the intersection between talents (inborn capacities), skills (acquired competencies), and interests (personality). When these three variables come together early in a person's career (or life), it is as if an emotional spontaneous combustion results. Psychologist Howard Gardner refers to this as a "crystallizing experience": an encounter with a field that is so profound and meaningful that it organizes and sparks all future efforts.

The developmental process of extraordinary achievement begins with immersing oneself in a field for the sheer joy of the immersion. Because the work fits so well with talents, skills, and interests, it no longer seems like work. It is a kind of purposeful play, but it is driven by what Maslow called the "peak experience"; by the sense of "flow" described by Csikszentmihalyi. Only later is this purposeful play channeled into directed efforts at mastery, through interactions with mentors. Developmentally, greatness begins in play.

It is ironic that most individuals fail to achieve their potential stature, not because they don't work, but because they have never found that purposeful play that results from crystallizing experiences. We fall into career fields without sampling what we'd truly love; we fall into trading styles based upon what we hear and what we're taught--not from purposeful play across markets and trading styles.

In Part One, I highlighted "constancy of purpose" as a crucial element of extraordinary achievement. This constancy doesn't come from guilt or even from normal motivation. It comes from a deep, emotional desire to sustain the flow experience by extending one's mastery. Every creator experiences a kind of runner's high and, like any runner, has to run every longer and faster to reach the experience. In that sense, greatness is a kind of positive addiction: it provides its own reward.

The longstanding truism in the research on greatness is that it takes at least a decade of dedicated effort to reach expert levels of performance in any field. That decade is typically guided by the mentorship of others who are accomplished, particularly as the developmental process proceeds from the achievement of competence to true expertise. In every performance field I have encountered, expert performers spend more time in learning, preparation, and practice than in actual performance. Indeed, their intrinsic levels of motivation drive them to do nothing but that. It is in the course of mastering a domain, that these performers master themselves and undergo deep psychological change. Mastery of any field inevitably also brings self-mastery.

The developmental process of extraordinary achievement begins with immersing oneself in a field for the sheer joy of the immersion. Because the work fits so well with talents, skills, and interests, it no longer seems like work. It is a kind of purposeful play, but it is driven by what Maslow called the "peak experience"; by the sense of "flow" described by Csikszentmihalyi. Only later is this purposeful play channeled into directed efforts at mastery, through interactions with mentors. Developmentally, greatness begins in play.

It is ironic that most individuals fail to achieve their potential stature, not because they don't work, but because they have never found that purposeful play that results from crystallizing experiences. We fall into career fields without sampling what we'd truly love; we fall into trading styles based upon what we hear and what we're taught--not from purposeful play across markets and trading styles.

In Part One, I highlighted "constancy of purpose" as a crucial element of extraordinary achievement. This constancy doesn't come from guilt or even from normal motivation. It comes from a deep, emotional desire to sustain the flow experience by extending one's mastery. Every creator experiences a kind of runner's high and, like any runner, has to run every longer and faster to reach the experience. In that sense, greatness is a kind of positive addiction: it provides its own reward.

The longstanding truism in the research on greatness is that it takes at least a decade of dedicated effort to reach expert levels of performance in any field. That decade is typically guided by the mentorship of others who are accomplished, particularly as the developmental process proceeds from the achievement of competence to true expertise. In every performance field I have encountered, expert performers spend more time in learning, preparation, and practice than in actual performance. Indeed, their intrinsic levels of motivation drive them to do nothing but that. It is in the course of mastering a domain, that these performers master themselves and undergo deep psychological change. Mastery of any field inevitably also brings self-mastery.

Sunday, June 11, 2006

Blueprint for an Uncompromised Life - Part One: Constancy of Purpose